The Lines of Others

March 24, 2024 Leave a comment

“There is something else which has the power to awaken us to the truth. It is the works of writers of genius. They give us, in the guise of fiction, something equivalent to the actual density of the real, that density which life offers us every day but which we are unable to grasp because we are amusing ourselves with lies.”

Simone Weil

Last year I spent several months with the Oblonskys, the Shcherbatskys, the Karenins, the Vronskys, the Levins, and a host of others. I did this, not as a foreign exchange student living in Russia, but as a mind traveler using the “guise of fiction” by a writer of genius.

Reading the 742 pages of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1878) was a way for me to experience humanity in another time and place.

In community with them, I saw how they lived. I saw what they saw. I heard what they said and thought. I learned what transpired from what they had said, thought and done. During my time with them, I became aware of the inner personality of each person and recognized matters of love and of good and evil that are timeless.

I watched Anna change from a warm and appealing person at the beginning of my stay into a small, spiteful, and self-absorbed woman at the end – all because of her vain imaginings about love and about how the world and those around her were thought to be. With ongoing self-deception, she came to think in terms of extremes and therefore made herself believe she understood everything and everyone in totality: it’s all the same and life was a Darwinian struggle for survival.

Looking back at my time with Anna, I see her narcissism, a personality disorder impacting many today, as a shrunken one-size-fits-me “temporal bandwidth” (see below). I learned a lesson from her toxic attitude: life is not about me.

Stiva, Anna’s hedonist brother, was consistently evil in an absence-of-good way. He forgets, neglects, and fails to act. He’s put his own household into chaos. He lives entirely in the present without regard for the effect he has on his family and future generations.

Dolly, Stivas’s wife, was a consistently good woman who showed self-giving love. She raised children married to such a husband.

Konstantin Dmitrievich Levin, over time, matured. He came to understand love as he watched his wife Kitty. And I witnessed Levin’s spiritual journey to faith in God.

A similar mind traveler experience occurred when I spent months in Russia with The Brothers Karamazov – Dmitri, Ivan and Alexei and their father Fyodor Pavlovich and his illegitimate son, Pavel Fyodorovich Smerdyakov. Agrafena Alexandrovna Svetlova, Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtseva, Ilyusha, and Father Zosima, the Elder also lived nearby. Quite a cast of characters when you get to know them and quite a legacy of behavior and thought they provide.

In Chekhov’s world of short stories, I shared in the experiences of many. I laughed, cried and saw myself in the everydayness of those I met along the way.

Why read 1800s novels Anna Karenina and The Brothers Karamazov and learn about people with weird names when I could have spent that time watching Yellowstone and taking in a C&W vibe? Why did I read Love in the Time of Cholera when I could have watched another car chase scene or another mindless comedy? Why did I read Death in the Andes when I could have watched a detective series. Why did I read My Antonia or Heart of Darkness or King Lear, for that matter, when I could have been on social media amusing myself? Why did I read anything outside my context as a Christian? Isn’t there some self-help personal growth book that will give a perspective on the world so I don’t have to venture out of a theological “safe space”?

I’ll give an answer a foreign exchange student would give for wanting an out-of-context experience:

“To interact with people from different cultures and to gain a deeper appreciation of their values, beliefs, and customs. To become more empathetic and understanding toward others, even those who are very different from me. To gain a better understanding of the diverse world we live in and develop a more open-minded perspective.”

Why read great literature from the past?

To rewire my brain from a competitive judgmental either/or reactionary mindset to a more deliberative way of thinking. To train my brain to think before leaping to conclusions. To employ such reading as a dopamine-hit buffer.

To gain the wisdom of those before me.

To grow faith and love. Imagination is required for faith. Imagination is cultivated by reading the unknown. Reading requires attentiveness. Love is attentiveness

To keep in mind that the prodigal son went looking for the Now thinking that anything could be better than what came before. He found the Now and it affirmed him to be a hungry desperate slave who longed to be fed what he fed the pigs (Luke 15:11-32).

To see another point of view and how it was arrived at.

To be a humanities archeologist. Everything came before Now. And up until broadcast media came around, all we had were the lines of others – words, music, and art.

To not be a reed in the wind. To cultivate “Temporal bandwidth” – “temporal bandwidth is “the width of your present, your now … The more you dwell in the past and future, the thicker your bandwidth, the more solid your persona. But the narrower your sense of Now, the more tenuous you are.”” – Alan Jacobs, To survive our high-speed society, cultivate ‘temporal bandwidth’

To not live as a presentist, as someone whose temporal bandwidth has narrowed to the instant something is posted on social media.

To imagine the future using what I learned from the past. For example, I read Solzhenitsyn to understand what it’s like to live under communism.

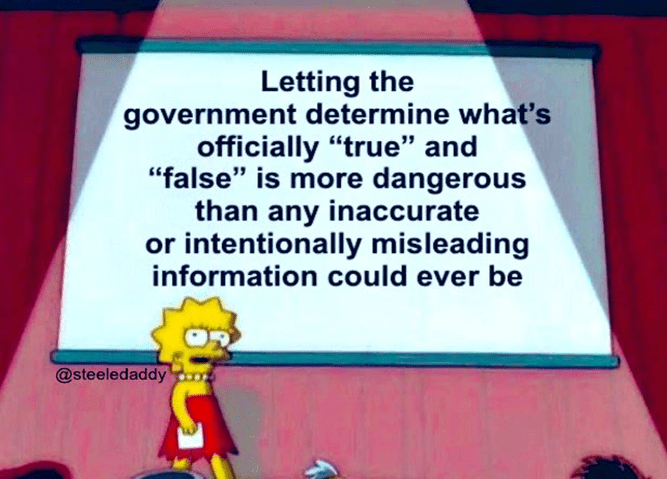

(If your temporal bandwidth is expanded even somewhat and you are not “amusing yourself with lies”, you see what was plotted before happening now. Joe Biden, along with abetting Globalist Progressives, is implementing the Cloward-Piven Strategy first developed in 1966. That strategy seeks to hasten the fall of capitalism by swarming the country with mass migration, overloading the government bureaucracy, creating a crushing national debt, have chaos ensue, take control in the chaos, and implement Socialism and Communism through Government Force.

To wit, beside the ongoing invasion of the U.S., our nation is incurring massive debt. There is the ongoing silencing of dissent by the DOJ, FBI, and social media cohorts. There is a push to impose digital IDs and digital currency along with WHO oversight to control us. The misanthropic handling of our lives should be a clarion signal to you that communist totalitarianism is coming!)

Books are safe spaces. But if you believe that words are violence (Toni Morrison in her Nobel prize address: “Oppressive language does more than represent violence. It is violence”) then you’ll stay in your “safe place” and refuse to be “breaking bread with the dead” (or listen to opposing views) where one can be an interlocuter and ask why and not just assume things and express rage.

I see going to a “safe space” as the closing in of one’s “temporal bandwidth” much like what Anna Karenina did. It has the exact opposite of a fortifying effect as one is made tenuous, anxious, and very susceptible to narcissism and Groupthink. (Ironically, that is also the effect of DEI.)

Here are two quotes from someone who championed the idea of Great Books, Allan Bloom that apply to what’s been said:

The most successful tyranny is not the one that uses force to assure uniformity but the one that removes the awareness of other possibilities, that makes it seem inconceivable that other ways are viable, that removes the sense that there is an outside.

The failure to read good books both enfeebles the vision and strengthens our most fatal tendency – the belief that the here and now is all there is.

Why read the realist fiction of writers such as Solzhenitsyn, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and others? To break bread with the dead and step out of my context into the lines of others.

Alan Jacobs, the Distinguished Professor of Humanities in the Honors Program at Baylor University and Senior Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture encourages what I call “mind travel” to the past in his book Breaking Bread with the Dead: A Readers Guide for a More Tranquil Mind.

What the book’s publisher said:

W. H. Auden once wrote that “art is our chief means of breaking bread with the dead.” In his brilliant and compulsively readable new treatise, Breaking Bread with the Dead, Alan Jacobs shows us that engaging with the strange and wonderful writings of the past might help us live less anxiously in the present—and increase what Thomas Pynchon once called our “personal density.”

Today we are battling too much information in a society changing at lightning speed, with algorithms aimed at shaping our every thought—plus a sense that history offers no resources, only impediments to overcome or ignore. The modern solution to our problems is to surround ourselves only with what we know and what brings us instant comfort. Jacobs’s answer is the opposite: to be in conversation with, and challenged by, those from the past who can tell us what we never thought we needed to know.

. . .

By hearing the voices of the past, we can expand our consciousness, our sympathies, and our wisdom far beyond what our present moment can offer.

In his web article To survive our high-speed society, cultivate ‘temporal bandwidth’, Alan Jacobs writes with regard to bolstering “personal density” (as derived in Mondaugen’s Law, Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow):

. . . benefit of reflecting on the past is awareness of the ways that actions in one moment reverberate into the future. You see that some decisions that seemed trivial when they were made proved immensely important, while others which seemed world-transforming quickly sank into insignificance. The “tenuous” self, sensitive only to the needs of This Instant, always believes – often incorrectly – that the present is infinitely consequential.

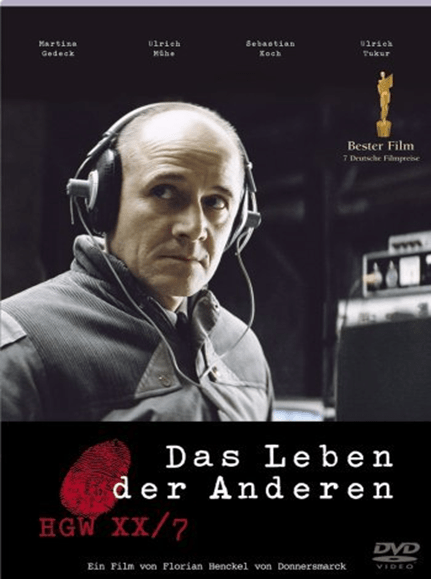

The title of this post is a reference to the 2006 movie The Lives of Others. The plot involves the 1984 monitoring of East Berlin residents by Stasi agents of the East German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler is told to conduct surveillance on playwright George Dreyman and his girlfriend, actress Christa-Maria Sieland. As Wiesler listens in from his attic post, he finds himself becoming increasingly absorbed by their lives. You’ll have to watch the movie to see if he is changed by listening to the lives and lines of others and becomes a “good man”.

~~~~~

Of course, the lines of others must include classical music, a rich and diverse soundscape. The soundscape of Now is constant noise.

Fauré: Elegy (Benjamin Zander – Interpretation Class) – YouTube

~~~~~

Reading for a More Tranquil Mind

Cherie Harder speaks with Alan Jacobs about the benefits of reading old books. Jacobs makes the compelling claim–using a phrase from Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow–that spending our time and attention on writers from the past can increase our “personal density.”

Episode 36 | Reading for a More Tranquil Mind | The Trinity Forum (ttf.org)

~~~

What if we viewed reading as not just a personal hobby or a pleasurable indulgence but as a spiritual practice that deepens our faith?

Reading as a Spiritual Practice (youtube.com)

~~~~~

Gary Saul Morson, a Dostoyevsky scholar, writes in a Plough article about Fyodor Dostoevsky and introduces a graphic novel adaptation of “The Grand Inquisitor” from The Brothers Karamazov.

Here is an excerpt:

In Dostoyevsky’s time, numerous schools of thought, ranging from English utilitarianism to Russian populism and socialism, maintained that they had discovered the indubitable solution to moral and social questions.

This way of thinking appalled Dostoyevsky. With his profound grasp of psychology, he regarded the materialists’ view of human nature as hopelessly simplistic. Deeply suspicious of what intellectuals would do if they ever gained the power they sought, he described in greater detail than any other nineteenth-century thinker what we have come to call totalitarianism. Even in its less terrifying forms, rule by supposedly benevolent experts was, he thought, more dangerous than people understood.

. . .

For Dostoyevsky, the Christian view of life, which most intellectuals regarded as primitive, offered a far more sophisticated understanding than materialist alternatives. . .. he regarded it as a profound mistake to rely only on technological solutions to social problems, a perspective that, if anything, needs to be challenged all the more strongly today. Man does not live by iPhone alone.

For more on The Brothers Karamazov see Jacob Howland’s article in The New Criterion: A realist in the higher sense | The New Criterion

~~~~~

Screen Captured or The Negative Effects of Social Media

JON HAIDT AND ZACH RAUSCH answer the question . . .

Why does it feel like everything has been going haywire since the early 2010s, and what role does digital technology play in causing this social and epistemic chaos?

. . . with their article What we’ve learned about Gen Z’s mental health crisis (afterbabel.com) and the included research-based articles:

Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic. Here’s the Evidence. By Jon Haidt

Here are 13 Other Explanations for the Adolescent Mental Health Crisis. None of them Work. By Jean Twenge

The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic is International, Part 1: The Anglosphere. By Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt

Why the Mental Health of Liberal Girls Sank First and Fastest. By Jon Haidt

Why I am Increasingly Worried About Boys, Too. By Jon Haidt

Play Deprivation is a Major Cause of the Teen Mental Health Crisis. By Peter Gray

Algorithms Hijacked My Generation. I Fear for Gen Alpha. By Freya India, and see also Do You Know Where Your Kids Go Every Day? By Rikki Schlott.

The Case for Phone-Free Schools. By Jon Haidt

Why Antisemitism Sprouted So Quickly on Campus. By Jon Haidt

A recommendation: NO smartphones for your children until at least 16 years of age. They can use a simple flip phone till then.

New book:

The Anxious Generation: HOW THE GREAT REWIRING OF CHILDHOOD IS CAUSING AN EPIDEMIC OF MENTAL ILLNESS by Jonathan HaidtHOW THE GREAT REWIRING OF CHILDHOOD IS CAUSING AN EPIDEMIC OF MENTAL ILLNESS

~~~~~