The Approaching Eclipse

March 3, 2024 Leave a comment

Imagine creating something significant and you make it public it and it is well-received. Then, State media (MSNBC and the NYT for example) pans it and you are declared an “enemy of Democracy.” The self-expression born of your life’s work, your name, and your personhood are to be eclipsed – blackened – by an authoritarian enforcement of new cultural norms. You are to be held hostage artistically and, if you do not conform, literally.

You realize that you can either abandon your life’s work out of fear of crushing reprisals, or you find a subversive way to bring your work to the public, as did one of the greatest composers of the 20th century.

“In January 1936, after Stalin attended a performance of [Dmitri] Shostakovich’s dangerously erotic opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, there appeared the notorious Pravda editorial ‘Chaos Instead of Music’, with its threat that things could ‘end badly’ for Soviet musicians – and for Shostakovich in particular. Its unnamed author was David Zaslavsky, a well-connected Soviet journalist and propagandist. No family was left untouched by the purges. The composer’s uncle, sister, brother-in-law and mother-in-law were arrested and when his patron, Marshal Tukhachevsky, was declared an ‘enemy of the people’, it is likely that he himself was interrogated by the NKVD. The musicologist Nikolay Zhilayev, to whom Shostakovich played the second movement in May 1937, had joined the disappeared by the time of the Fifth’s Leningrad premiere on November 21, 1937.” – David Gutman, Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony: A deep dive into the best recordings | Gramophone

The opera was attacked as “muddle instead of music” in an editorial, probably written by Stalin himself, in the Communist Party newspaper, Pravda. If Shostakovich did not turn away from the “decadent” avant-garde in favor of Soviet Realism, threatened the editorial, “things could end very badly.” The popular opera disappeared from the stage overnight. One of the Soviet Union’s most prominent composers was in danger of becoming a “nonperson” just as he was reaching his artistic prime. –Timothy Judd, writing in Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony: The Unlikely Triumph of Freedom

After the vicious official attack, Shostakovich lived in constant fear. Conductor, composer, music director, and arranger Benjamin Zander, writes

Overnight the 30-year-old composer’s rapidly ascending star plummeted. He came to regard himself, and to be regarded, as a doomed man, waiting with packed bags for the secret police to take him away during the night. In fact, the police never came, but the fear of official reprisals for any displeasure which his music might occasion coloured every moment of his life after that. He was never to know freedom again, except surreptitiously in some of his music.

Knowing that at any moment the authoritarian Soviet State might find fault with his music and then imprison him and his family, Shostakovich looked for a way to continue to work within the overshadowing Stalinist system.

“Shostakovich attempted to restore himself to the good graces of the Soviet critical establishment with “a conscious attempt to create a simplified ‘Socialist realist’ style that could be acceptable both to the Party and to the intelligentsia.” (Source)

And so, knowing that his latest effort would not be accepted (written in 1936, but not publicly performed until 1961) . . .

Shostakovich withdrew the Fourth Symphony from its scheduled performance and began the composition of a fifth which had as its [imposed by the State] subtitle, ‘An artist’s practical answer to just criticism’. His intention was to reinstate himself, through this work, in the eyes of the Politburo. The Fifth Symphony did indeed do that: the first performance was a huge success. It is anything but cheerful: the first movement is dark and foreboding, the second is ironic and brittle, and the third a deep song of sorrow. However, only the message at the end was important to the Soviets, and Shostakovich knew that. The long final movement, as they heard it, climaxed in a triumphant march, a paean of praise to the Soviet State.– Benjamin Zander

Was the Fifth Symphony to be understood as essentially Stalinist? There was more to the forced empty pomp of the fourth movement than met the Politburo’s ears.

“In [Solomon Volkov’s 1979] Testimony, Shostakovich fiercely renounces all this, in particular denying that the Fifth’s finale was ever meant as the exultant thing critics took it for: “What exultation could there be? I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat, as in Boris Godunov. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,’ and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ‘Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.’ What kind of apotheosis is that? You have to be a complete oaf not to hear that.” -Samuel Lipman, writing in Shostakovich decoded? | The New Criterion (Emphasis mine.)

Was the Fifth Symphony a subversive symphonic response to Stalin, one that both mocks the dictator while bowing to him?

In the remarkable finale, Shostakovich achieves one of the greatest coups of his symphonic career: a “victorious” closer that drives home the expected message and at the same time makes an entirely different point — the real one. The resounding march that ends the movement represents the triumph of evil over good. The apparent optimism of the concluding pages is, as one colleague of the composer put it, no more than the forced smile of a torture victim as he is being stretched on the rack. (Source)

Shostakovich publicly described the new work as “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism.” Privately, he said (or is said to have said) that the finale was a satirical picture of the dictator, deliberately hollow but dressed up as exuberant adulation. It was well within Shostakovich’s power to present a double message in this way, and it is well beyond our means to establish whether the messages are true or false. The listener must read into this music whatever meaning may be found here; its strength and depth will allow us to revise our impressions at every hearing. (Source)

Did Shostakovich openly camouflage* a subversive message in the forced celebration of the fourth movement? The finale was not what it seemed.

Mark Pettus, in Pushkin and the Key (?) to Shostakovich’s 5th writes:

“In his official comments on his symphony, Shostakovich said the following:

“”I wanted to show in my symphony how, through a series of tragic conflicts, of great internal spiritual struggle, optimism as a worldview finds its affirmation.”

“The affirmation of “optimism as a worldview” — what a grotesque phrase! Farewell, spiritual struggle! It would seem impossible to accept this account of what the music “means” — and yet this interpretation seems to have been swallowed whole by the establishment; the work was praised, and Shostakovich’s “rebirth” as an ideologically acceptable composer was complete. And, indeed — music being what it is — the symphony seems to offer no objective reason for doubting the official reception. After all, isn’t the triumph of the finale… triumphant?

“. . . if things were so straightforward, then what made Pasternak, who was in the audience at the premiere, supposedly say the following:

“”And to think that he said everything he wanted to, and nothing happened to him!””

Shostakovich, with a motif from his own Four Romances on Poems by Pushkin, Op. 46: I. Rebirth, had inserted a Pushkin reference into the fourth movement. The poem-motif attacked Stalin and his ways and went on to express that over time, his work which had been defaced, will survive even the most brutal oppression and defilement. The reference heralded his own “rebirth”, as an ideologically acceptable composer and as a resurrected artist.

Rebirth (Alexander Pushkin)

A barbarian artist, with his indolent brush,

Blackens the painting of a genius,

And, atop it, he senselessly traces

His lawless drawing.

But, over the years, these alien layers of paint

Are shed like old scales;

Before us, the genius’s creation

Emerges with its former beauty.

Thus do delusions vanish

From my tormented soul,

And in it visions arise

Of primal, pristine days.

In the podcasts below, you’ll hear conductor Joshua Weilerstein explore the four movements of Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony.

* “Time and again, Tolstoy uses this technique of open camouflage. He does so, I think, so that we learn not to equate noticeability with importance and so that we acquire, bit by tiny bit, the skill of noticing what is right before us.” – Gary Saul Morson, The Moral Urgency of Anna Karenina – Commentary Magazine

~~~~~

Playing the fourth movement (Allegro Non Troppo) of Shostakovich’s 5th in high school concert band, I had no idea of the circumstances under which it had been composed – an artist threatened with suppression and persecution. I had no idea of the Pushkin reference hidden in the work. As first trumpet, all I knew was that it was a brass-forward piece of music. But now, I notice what was right before me and that has expanded my temporal bandwidth enough to see the approaching eclipse.

The barbarian artists of our day – Progressives and the Biden regime – with indolent brushes, blacken any expression, any individual, and any name that will not conform to its strictures and senselessly traces lawless drawings upon the works of truth, beauty, and goodness using the media, the administrative state, the CIA, the DOJ, and Taylor Swift.

Reason doesn’t suit the appetite of most. Artists, writers, playwrights, poets, journalists, composers, and musicians must work to subvert the approaching eclipse of humanity by the State, the WHO, the WEF, AI, transhumanism, and communism.

~~~~~

“This was not the Moral Majority of my father’s era. Rather, this was a subversive, courageous subculture that was resisting the dominant narrative, and the morass of darkness that is our dominant cultural moment.” – Dr. Naomi Wolf: “Letter from CPAC”

~~~~~

Here is the State eclipsing a journalist. . .

And here is State approved writing that blackens individuals . . .

~~~~~

Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, Part 1

Shostakovich’s life and career was so wrapped up with his relationship to the Soviet government that it is sometimes hard to appreciate that, all else aside, he was one of the great 20th century composers. His 5th symphony is the meeting point between Shostakovich’s music and the political web he was often ensnared in, and it is a piece that is still being vociferously debated. This week we’re going to tell the story of the piece’s genesis, and then we’ll explore the movements of the symphony.

Sticky Notes: The Classical Music Podcast: Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, Part 1 (libsyn.com)

Sticky Notes: The Classical Music Podcast: Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, Part 2 (libsyn.com)

~~~~~

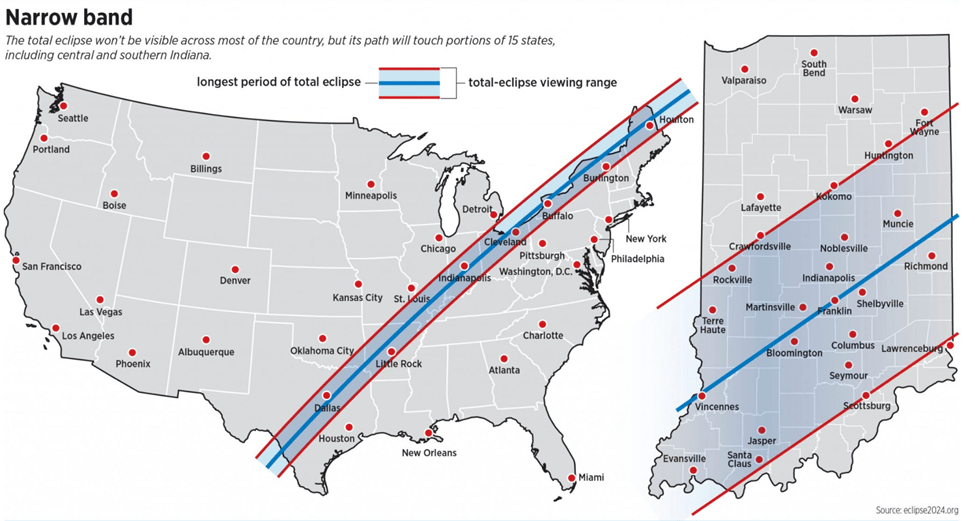

Solar Eclipse – April 8th, 2024

How southern Indiana communities are preparing for the 2024 solar eclipse – Inside INdiana Business

2024 Total Solar Eclipse Planning Toolkit: INDIANA UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR RURAL ENGAGEMENT

2024 eclipse guide: Times, places, states and livestream (astronomy.com)

“Photographing the Eclipse” Rick Galloway, IAS Member Rick gives a presentation on how photograph the eclipse and not miss it by doing so.

IAS February 2024 General Meeting – YouTube