Uncharted Understanding

June 16, 2024 Leave a comment

Hadn’t things already been mapped out? Most thought they knew the system of cosmic order and justice in a world of evil, suffering, and chaos. But the course they followed, was it determined by superstitious and romantic assumptions?

Someone had a novel idea: write a prose tale of events and characters employing an extreme case to exemplify, expand, and examine common notions at the time. What was created is similar to a parable.

The conventional wisdom was that you take care of the gods through ritual and they take care of you. You forget the gods and the gods got angry. And then one had to work to appease the gods to regain favor and benefits. This quid pro quo piety-for-prosperity symbiosis between contingent and capricious gods and mankind was considered the foundational principle in the cosmos. It was thought to represent order and justice in the cosmos.

Two particular issues were scrutinized by the author. (1) Was the Retribution Principle (RP) – the righteous will prosper and the wicked will suffer – the foundational principle of the cosmos? (2) Does anyone serve God for nothing?

The characters or figures in the fictional account:

The Arbiter – a character representing God

The Challenger. His function was adversarial: to point out issues with people and policies and to present arguments against a person or policy.

Job, a ritually pious man and the subject of the problem posed.

Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar, and Elihu. They are Job’s friends, counselors, advice givers, and challengers.

An unnamed friend of the heavenly court. He offers supplemental material.

The following is a brief summary of the account:

One day the Arbiter was holding court. Heavenly beings were there to report on what was going on in the cosmos. Among them was the Challenger.

The Arbiter pointed out Job to the Challenger. There was no on quite like him, he said. He considered Job to be honest through and through, a man of his word, totally devoted to him, and someone who hated evil with a passion. Job even made sacrificial atonement to the Arbiter for his children just in case they sinned during their partying.

Knowing that Job was incredibly wealthy and the most influential man in all the East, the Challenger alleged that a self-interest symbiosis with the Arbiter motivated Job. Righteous people like Job behaved righteously, he contended, because of the expectation of a reward from the Arbiter.

Was this true? Was the Retribution Principle the Arbiter’s policy? Was reward Job’s motivation to be righteous? Does Job serve God for nothing? The Challenger wanted to find out. He picked Job to be the unwitting focus of his posed problematic policy:

“So do you think Job does all that out of the sheer goodness of his heart? Why, no one ever had it so good! You pamper him like a pet, make sure nothing bad ever happens to him or his family or his possessions, bless everything he does—he can’t lose!

“But what do you think would happen if you reached down and took away everything that is his? He’d curse you right to your face, that’s what.”

With the Arbiter’s go ahead, Job, a blameless and upright man was exposed to devastating loss. Yet, in spite of losing everything including his sons and daughters, Job maintained his integrity. And, he didn’t blame the Arbiter.

Seeing the failed result of this trial, the Challenger wanted to further test his proposition – that righteous behavior is based on physical blessing:

“A human would do anything to save his life. But what do you think would happen if you reached down and took away his health? He’d curse you to your face, that’s what.”

The Arbiter once again gave the go ahead but with the condition that Job does not lose his life in the process. Job was then struck with terrible sores. He had ulcers and scabs from head to foot. He used pottery shards to scrape himself. He went and sat on a trash heap among the ashes. Job was in extremis.

And it was there, among the ashes, that Job gets his first feedback into the horrendous situation that he finds himself and has had no control of:

His wife said, “Still holding on to your precious integrity, are you? Curse God and be done with it!”

Job’s wife responded with imperatives to her husband: accept the tragic situation, curse God, and accept the fate of death – in effect, “life is not worth living Job”. It should be noted that if Job does what she says, the Challenger’s claim would be proven true: benefits had motivated him all along. But Job tells her that she is out of line:

“You’re talking like an empty-headed fool. We take the good days from God—why not also the bad days?”

The study records that after all that had been inflicted on Job, he remained blameless and said nothing against the Arbiter.

Included in this tale are three cycles of dialogs that Job had with his three friends Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar. These three heard of Job’s situation and came to console him. When they saw him, it was written, they sat quietly mourning. They thought Job was on the way out.

Later, after days of silence, they each in turn offer Job their worldly wisdom about his dire state. They believed there was something off about him and his thinking. So, they each try to find fault with Job and they each reaffirm the Retribution Principle in the process.

The Arbiter, they tell Job, protects the righteous and punishes the wicked. Regarding the reason for his suffering, they tell Job that no mortal is righteous and how can mortals understand what the Arbiter demands.

Their advice to Job: put away sin, restore your righteousness, plead your case before the Arbiter, and regain benefits. Notably, their counsel was contrary to Job’s wife’s directive when she told her husband to just be done with the RP and die. The friends, like Job’s wife, do tell Job to accept the tragic situation but they want him to revise his thinking and his life and then he will find that life is worth living through restored benefits.

The three friends counsel was in line with the Challenger’s claim: there’s a symbiotic relationship between piety and prosperity. To defend this principle, they reject any notion of Job’s righteousness. For them, the end game was material reward.

If Job acted in accord to what his three friends said, he would validate the Challenger’s claim. But Job has not been swayed by their words directing him back to benefits. He has shown that his righteousness stands apart from benefits. And so, the three friends are silenced.

Job does question the Arbiter’s justice:

“Does it seem good to you to oppress, to despise the work of your hands and favor the schemes of the wicked?”

In saying his suffering is undeserved, Job claims that what has happened to him cannot be justified by his behavior. He thinks the RP system of justice is broken and the Arbiter is being petty.

The dialog with the three friends ends with them not finding fault with Job’s behavior. Job maintained his innocence all along. He had done nothing wrong and admitted to no wrong doing. And Job does not expect any benefit or reward. He does serve the Arbiter for nothing. As such, he refutes the Challenger’s claim.

In standing by his righteousness, Job believed there was an advocate or mediator (a redeemer) who would show up and vindicate him. This seems to be Job pointing a finger at the Arbiter and wanting the Arbiter to justify his actions to Job. The Arbiter remained silent throughout the dialogs.

After the dialogs, supplemental material is inserted. Someone who has not been involved (an unnamed friend of the heavenly court?) offers poetic insight that speaks to the cosmic issues raised. He provides perspective from territory not explored in the dialogs.

He asks “Where do mortals find wisdom? and “Where does insight hide?” And he answers: “Mortals don’t have a clue, haven’t the slightest idea where to look.”

With what’s been dug up so far in the dialogs, these questions raise issues: what man has found- the Retribution Principle – is this the foundational principle of order in the cosmos? Is justice the foundational principle of the cosmos? If neither is true, then what is?

The supplemental material would have us understand that the foundational principle of the cosmos is wisdom and not justice. And, that the Arbiter alone knows the exact place to find wisdom. For the Arbiter is the only source of wisdom and its only evaluator.

The poem states that the Arbiter, after focusing on wisdom and making sure it was all set and tested and ready, created with wisdom thereby bringing order and coherence to the cosmos. What’s man to do? Totally respect the wisdom of the Arbiter. Insight into that wisdom means shunning evil

After this poetic insert there are three speeches.

Job begins by pining for the past: “Oh, how I long for the good old days, when God took such very good care of me.” The RP was working and things seemed coherent. He was in a good place then and in good standing socially.

“People who knew me spoke well of me; my reputation went ahead of me. I was known for helping people in trouble and standing up for those who were down on their luck.”

But now, Job says, things are not good. His role and status in society has reversed – from honor to dishonor. He’s the butt of jokes in the public square. He’s mistreated, taunted and mocked. And the Arbiter has remained silent. He laments:

“People take one look at me and gasp.

Contemptuous, they slap me around

and gang up against me.

And the Arbiter just stands there and lets them do it,

lets wicked people do what they want with me.

I was contentedly minding my business when the Arbiter beat me up.

He grabbed me by the neck and threw me around.

For Job, things are incoherent. It’s a dark night for Job’s soul. He feels abandoned, empty, and desolate along with enduring extreme physical agony.

The trauma he is experiencing may have scrambled his senses. He lashes out at the Arbiter:

“I shout for help, you, and get nothing, no answer! I stand to face you in protest, and you give me a blank stare!”

“What did I do to deserve this?” he says. “Haven’t you seen how I have lived and every step I take?”

Job tries to restore coherence with an oath of innocence. He lists forty-two things that he is innocent of and then pleads for a vindication scenario: “Oh, if only someone would give me a hearing! I’m prepared to account for every move I’ve ever made – to anyone and everyone, prince or pauper.”

As things seem to be out of control, Job considers the Arbiter something of a wild card, an unknown or unpredictable factor. He’s being capricious like all the other gods.

After Job speaks, another friend enters the conversation. Elihu, younger than the others, has been waiting and listening to the conversation. He’s somewhat brash in addressing the group. Elihu, in a somewhat superior way, wants Job and the others to know that he is speaking on behalf of the Arbiter.

“Stay with me a little longer. I’ll convince you.

There’s still more to be said on God’s side.

I learned all this firsthand from the Source;

everything I know about justice I owe to my Maker himself.”

Elihu is angry with the older three friends. They had condemned Job and yet were stymied because Job wouldn’t budge an inch—wouldn’t admit to an ounce of guilt. And they ran out of arguments. He contends that the wisdom of their many years – the conventional thinking about the self-interest symbiosis and the carrot sticks of the Retribution Principle – did nothing to refute Job.

Elihu presents another accusation angle and it’s not the motivation claim of the Challenger. He starts by repeating Job’s words:

“Here’s what you said.

I heard you say it with my own ears.

You said, ‘I’m pure—I’ve done nothing wrong.

Believe me, I’m clean—my conscience is clear.

But the Arbiter keeps picking on me;

he treats me like I’m his enemy.

He’s thrown me in jail;

he keeps me under constant surveillance.’”

Job thought that he was being scrutinized way too much by the Arbiter. He was being excessively attentive and petty.

Elihu is angry at Job for justifying himself rather than God. Job, he claims, regards his own righteousness more than the Arbiter’s and is therefore self-righteous and proud. That is why he is suffering. And, his suffering, Elihu claims, may not be for past sins but as a means to reveal things now to keep him from sinning later.

Elihu heard Job questioning the Arbiter’s justice: Job was not happy about a policy where the righteous suffer; something was off with the RP system or its execution. Job thought that the Arbiter could do a better job of things. Job, claims Elihu, doesn’t know what he is talking about and speaks nonsense.

He comes at Job with a defense of the transcendence of the Arbiter.

“The Arbiter is far greater than any human.

So how dare you haul him into court,

and then complain that he won’t answer your charges?

The Arbiter always answers, one way or another,

even when people don’t recognize his presence.”

And,

“Take a long, hard look. See how great he is—infinite,

greater than anything you could ever imagine or figure out!

Against Job’s “senseless” claims, Elihu says that the Arbiter is not accountable to us. The Arbiter is not contingent and not bound to our scrutiny. In a break with the conventional wisdom – the quid pro quo piety-for-prosperity symbiosis with the gods – Elihu says that neither righteousness and wickedness have an effect on the Arbiter.

The Arbiter, he says, “is great in power and justice.” He uses nature to explain:

“It’s the Arbiter who fills clouds with rainwater

and hurls lightning from them every which way.

He puts them through their paces—first this way, then that—

commands them to do what he says all over the world.

Whether for discipline or grace or extravagant love,

he makes sure they make their mark.”

Elihu wants Job to know that no one can out-Arbiter the Arbiter. He poses a theodical reason for Job’s suffering –the Arbiter’s justice. And that is how he tries to introduce coherence to Job’s situation. He thinks justice is the foundational principle of the cosmos.

Elihu’s justice and cosmic order also includes the RP. At one point he tells Job that if people listen and serve the Arbiter, they will complete their days in prosperity and their years in pleasantness.

Finally, from out of a whirlwind, the Arbiter speaks. He remains silent about Job’s oath of innocence.

Starting with “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?” the Arbiter asks Job rhetorical questions which reveal the utter lack of understanding of those who thought they knew how the complex cosmos was ordered.

“Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?”

“Have you ever in your days commanded the morning light?”

“Where does light live, or where does darkness reside?”

“Can you lead out a constellation in its season?”

Job and friends had reduced cosmic order to be a mechanical system of automatic justice: the Retribution Principle. The Arbiter would have Job know that he and his friends don’t know all the ins and outs of how the cosmos is ordered including why there is suffering. And that he is not to be defined and held accountable by their systems of thought.

After detailing some of the knowledge and intricate design that went into the ordered cosmos, a cosmos that encompasses the yet-to-be ordered, the disordered, and wild things, the Arbiter then corners Job: “Now what do you have to say for yourself? Are you going to haul me, the Mighty One, into court and press charges?” The Arbiter agrees with Eliphaz’s assessment of Job: Job is self-righteous.

Job responds: “I’m speechless, in awe—words fail me. I should never have opened my mouth! I’ve talked too much, way too much. I’m ready to shut up and listen.”

The Arbiter challenges Job: “Do you presume to tell me what I’m doing wrong? Are you calling me a sinner so you can be a saint? Go ahead, show your stuff. Let’s see what you’re made of, what you can do. I’ll gladly step aside and hand things over to you—you can surely save yourself with no help from me!”

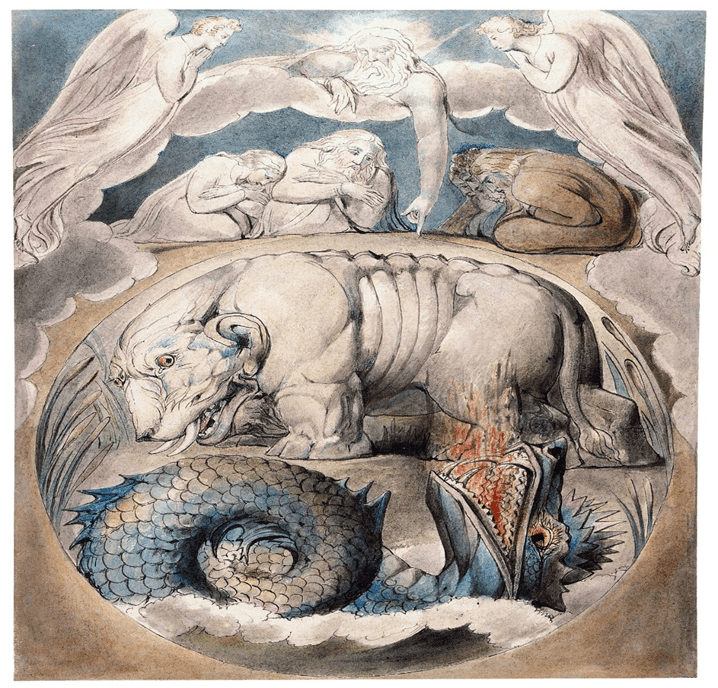

To exemplify their differences and respective roles, the Arbiter instructs Job with examples of imaginative creatures seemingly both natural and mythical: Behemoth and Leviathan

Job is compared to Behemoth: “Look at the land beast, Behemoth. I created him as well as you. Grazing on grass, docile as a cow . . .”

Behemoth is content and well-fed, strong, first of its kind, cared for, sheltered, not alarmed by turbulence. Behemoth is an example of stability and trust: “And when the river rages, he doesn’t budge, stolid and unperturbed even when the Jordan goes wild.”

The Arbiter is compared to Leviathan, the sea beast with enormous bulk and beautiful shape.

“Who would even dream of piercing that tough skin or putting those jaws into bit and bridle?”

Leviathan can’t be tamed or controlled and should not be challenged or messed with. “There’s nothing on this earth quite like him, not an ounce of fear in that creature!”

The Arbiter has drawn a vast distinction between himself and Job.

Job had been speaking about his own righteousness and God’s justice. Behemoth is not an example of righteousness or of a questioning attitude. Rather, Behemoth is an example of stability amidst turbulence (crisis). Behemoth symbolizes creaturely trust.

Leviathan, not an example of justice, is the image of a rather terrifying creature. There is nothing wilder than the Leviathan. Leviathan cannot be domesticated. It would be utter folly to tangle with such a creature.

After the Arbiter finishes his description of Leviathan, Job answers:

You asked, ‘Who is this muddying the water,

ignorantly confusing the issue, second-guessing my purposes?’

I admit it. I was the one. I babbled on about things far beyond me,

made small talk about wonders way over my head.

You told me, ‘Listen, and let me do the talking.

Let me ask the questions. You give the answers.’

I admit I once lived by rumors of you;

now I have it all firsthand—from my own eyes and ears!

I’m sorry—forgive me. I’ll never do that again, I promise!

I’ll never again live on crusts of hearsay, crumbs of rumor.”

The Arbiter accepts Job’s admission that he was both ignorant and wrong about the Arbiter. Job has grown in his understanding: justice is not automatic – good is not rewarded and evil punished mechanically. The Arbiter is not a contingent being. He is not beholden to Job. He is not accountable to Job. Job cannot force the Arbiter to act.

The Arbiter, who heard Elihu say true things about the Arbiter, addresses Eliphaz:

“I’ve had it with you and your two friends. I’m fed up! You haven’t been honest either with me or about me—not the way my friend Job has!”

The Arbiter tells them to go to Job and sacrifice a burnt offering on their own behalf and Job will pray on their behalf – just as Job did for his own children just in case they’d sinned. The Arbiter accepts Job’s prayer.

After Job had interceded for his friends, God restored his fortune—and then doubled it! Job’s later life was blessed by the Arbiter even more than his earlier life. He lived on another 140 years, living to see his children and grandchildren—four generations of them! Then he died—an old man, a full life.

Job’s restoration at the end does not make up for the losses he incurred. The restoration seems to reset the stage for Job to bring the understanding he gained during his suffering to a new generation. He will tell his daughters to have Behemoth-like trust in the Arbiter and not in a mechanical system of justice.

He may even tell them that prayer is not a cause-and-effect mechanism. Prayer is listening to God.

~~~

As we find out, this fictional tale is not an answer as to why there is suffering or benefit, for that matter. The author’s narrative was meant to educate and expand the reader’s understanding of Yahweh in a world where there are things that make people suffer. Its purpose was to challenge conventional thinking about order, justice, and Yahweh.

The narrative asked questions: Is the Retribution Principle (RP) – the righteous will prosper and the wicked will suffer – the foundational principle in the cosmos? And, does anyone serve the Arbiter for nothing?

The first question is answered through two contrasted views of reality: the old-time religion of piety-for-prosperity as order and justice in the cosmos and the Arbiter’s Wisdom as being the foundational principle in the cosmos. The second question is resolved by Job.

He continued to serve the Arbiter (and did not curse him as the Challenger supposed would happen) during his suffering. He did so without expectation of reward thereby rejecting the piety-for-prosperity symbiosis that was thought to exist between the gods and man.

We find out that the Arbiter, not Job, is put on trial. Under great suffering, Job questioned the Arbiter’s policies. He wondered if the Arbiter was petty and unjust.

The Arbiter, with no need to defend himself, corrects Job. For, Job did not begin to understand what’s involved in the mysteries of creation nor about cosmic order and justice. Job and his friends were not the source of Wisdom.

The Arbiter, along with the supplemental “wisdom” poetry, raised Job’s and the reader’s focus on suffering – the “raging waters” – up to great heights – the uncharted territory of creation beyond man’s comprehension where one would find a Leviathan-like being beyond our control.

This brief summary does not begin to extract the wealth of wisdom and understanding found in Dr. John Walton’s study of the book of Job:

Job (The NIV Application Commentary): Walton, John H.: 9780310214427: Amazon.com: Books

Dr. John Walton, Job (30 mini-lectures) – YouTube

How should we understand our world?

Session 25: The World in the Book of Job: Order, Non-order, and Disorder by John Walton from Dr. John Walton, Job (30 mini-lectures) – YouTube

John H. Walton (Ph.D., Hebrew Union College) is professor of Old Testament at Wheaton College. Previously he was professor of Old Testament at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, Illinois.

Bibliography: Block, Daniel I., ed. Israel: Ancient Kingdom or Late Invention? Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2008; Longman, Tremper III, and John H. Walton. The Lost World of the Flood: Mythology, Theology, and the Deluge Debate. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2018; Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Second edition. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2018; idem. Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2011; idem. Old Testament Theology for Christians: From Ancient Context to Enduring Belief. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2017; idem. The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest: Covenant, Retribution, and the Fate of the Canaanites. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2017; idem. The Lost World of the Torah: Law as Covenant and Wisdom in Ancient Context. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2019.

~~~~~

“The suffering and evil of the world are not due to weakness, oversight, or callousness on God’s part. But rather, are the inescapable costs of a creation allowed to be other than God.” – John Polkinghorne

~~~~~

In light of the severe suffering and trauma that Job is exposed to, some may see the Arbiter’s response as cold and clinical, unfeeling and even autistic. Some in this day and age may hold that feelings and victimhood are core principles for understanding the world and may bad mouth the Arbiter for not being empathetic. Some might assert that his response is not their version of the RP’s justice and order- social justice. They may want an Arbiter to express himself like they do. Finding out that the Arbiter is beyond all reckoning unsettles them.

~~~~~

The Uncertainty Specialist with Sunita Puri

Pain is like a geography—one that isn’t foreign to palliative care physician, Dr. Sunita Puri. Kate and Sunita speak about needing new language for walking the borderlands and how we all might learn to live—and die—with a bit more courage.

In this conversation, Kate Bowler and Sunita discuss:

How to walk with one another through life’s ups and downs—especially health ups and downs

What “palliative care” means (and how it is distinct from hospice)

The difference between what medicine can do and what medicine should do

Sunita’s script for how to talk to patients facing difficult diagnoses

Sunita Puri:The Uncertainty Specialist – Kate Bowler

~~~~~

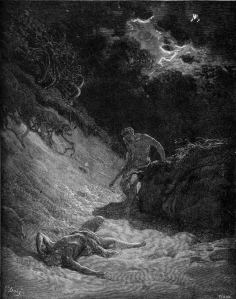

“Here be dragons” (Latin: hic sunt dracones) means dangerous or unexplored territories

“Here be Dragons” was a phrase frequently used in the 1700s and earlier by cartographers (map makers) on faraway, uncharted corners of the map. It was meant to warn people away from dangerous areas where sea monsters were believed to exist. It’s now used metaphorically to warn people away from unexplored areas or untried actions. There are no actual dragons, but it is still dangerous.

The Psalter world map with dragons at the base: