A Bugger’s Life

June 22, 2025 Leave a comment

What’s bugging Harry Caul?

Harry, a professional eavesdropper, is being paid to spy on a woman having an affair. But something he overheard makes him question whether he can remain a detached listener.

Harry and his crew use powerful microphones to record a conversation between the woman and her lover as they walk around a crowded San Francisco square. Later, after filtering out background noise on the tape, Harry replays a cryptic phrase in the recording. He imagines it to mean that the woman is being targeted to be murdered by his client.

Listening to his conscience, already replaying guilt and shame from a previous snooping assignment, Harry looks for a way out, for a way to not have blood on his hands. To offload his responsibility, he confides to a priest in a confessional, the oldest form of eavesdropping:

I’ve been involved in a job that may bring misfortune to two young people. It’s happened before. What I do has caused harm to someone. I’m afraid it will happen this time too. I’m not responsible for it. I can’t be responsible for it.

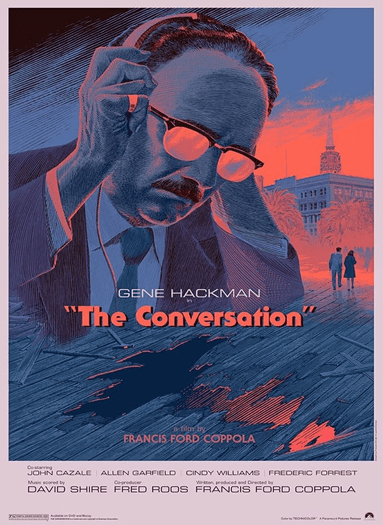

The conversation in the park and in Harry’s soul takes place in the 1974 film by Francis Ford Coppola – a tense thriller and character study titled The Conversation.

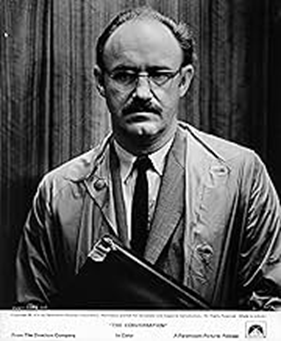

Gene Hackman (God rest his soul) plays Harry Caul, ‘the best bugger on the West Coast.’ Harry is obsessed with technology and works in a world where privacy can be bought and sold using it.

On-the-job Harry, a surveillance expert, is an invader of privacy. He gets paid to move in close, take pictures, and record private conversations with electronic devices. But Harry has a paranoid fear of anyone being up close and personal with him.

Harry guards his privacy. He lives in a sparsely furnished apartment that is secured by three locks and an alarm system. It’s his fortress. He uses a payphone to make personal calls and lies about having a home telephone. Alone, Harry spends time playing his saxophone along with jazz records. Jazz is the music of individualists and loners.

Harry looks like a regular Joe. He easily fits into crowds and isn’t noticed while snooping. But Harry isn’t public. The enigmatic Harry stays emotionally detached from others, cut him off from the rest of the world as though he’s not really a part of it yet. This suggested in his last name “Caul,” the thin membrane that surrounds a fetus until it is born. His translucent raincoat suggests the caul.

Harry’s work is intrusive, but he wants protection from the same. He avoids below-the-surface relationships with people in his industry, his coworker Stan (John Cazale), and Amy, the mistress he supports and visits at random times.

Harry records private moments between humans. But the guarded Harry can’t or won’t expose himself to another human. His involvement with Amy (Teri Garr) is not a relationship nor intimacy. Harry shows up on his birthday and Amy thinks it is a good time to get to know Harry, to know his secrets. But Harry says he has no secrets to his secret lover. Harry is distant even from the person he is physically closest to.

As with the priest, Harry off loads his conscience and distances himself from the detrimental effects of his work. When Stan wants to speculate about the meaning of the conversation between Ann and Mark on the tapes, Harry insists that it is just a job and that it is unprofessional to get too curious or assume anything. How ironic for the intensely curious Caul!

Stan: It wouldn’t hurt if you filled me in a little bit every once in awhile. Did you ever think of that?

Harry Caul: It has nothing to do with me! And even less to do with you!

Stan: It’s curiosity! Did you ever hear of that? It’s just g*ddamn human nature!

Harry Caul: Listen, if there’s one sure fire rule that I have learned in this business is I don’t know anything about human nature. I don’t know anything about curiosity. That’s not part of what I do.

The man who hires Harry is Martin Stett (Harrison Ford). Stett is the assistant to Harry’s client, the director (Robert Duvall). Initially, Stett is friendly. But when Harry refuses to hand over the tapes, he becomes intimidating and warns Harry to “be careful.” He surveils Harry at the surveillance tech convention.

After a party at his workshop, Harry spends the night with Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae), a woman he has just met. He finds out the next morning that the tapes have been stolen. Stett had Meredith steal the tapes.

Stett tells Harry that they couldn’t wait for the tapes. He then tells Harry to come to the director’s office to hand over the photographs and collect his money. There, Harry meets the director and realizes that the woman he has been spying on is the director’s wife. The taped conversation now seems to signal the worst for the woman.

After leaving the office, Harry decides to get involved. His Catholic conscience kicks in and so does his covert curiosity. He surveils the lovers in a hotel room and . . .

I’ll stop there, with the basic elements of the film. You can watch the movie, experience the intrigue, check out the enigmatic Harry Caul character, and find out what’s bugging Harry Caul.

~~~

Some questions and thoughts:

Does Harry’s method of recording reality, a cryptic conversation here, turn out to be flawed?

Does anyone who views or hears another from a distance – do they know that person? Or, do they only hear and see what they want to.

Do devices divine truth?

Does Harry compartmentalize his work-self from his conscience so as to maintain his addiction to snooping?

Does Harry become a pawn in another scheme?

Does Harry become a “partner in crime” that he so wanted to avoid?

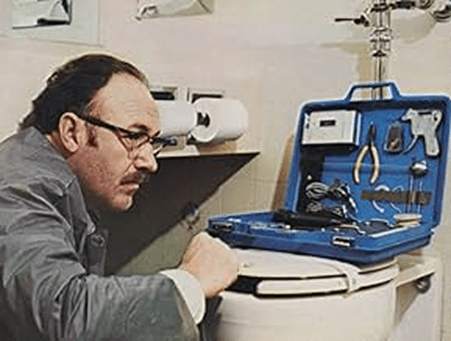

Does the overflowing toilet scene signify the ugly truth coming to the surface?

How does super snoop Harry end up at the end of the movie? What’s his psychological state? What does his utter helplessness represent?

In the end, with what’s left intact, does Harry Caul find what is ‘bugging’ him? Does Harry come up empty?

Why would a Christian and book reader like me watch this movie? Well, for one reason, it is a great movie.

The Conversation, written, produced, and directed by Francis Ford Coppola between the Godfather movies, is a tense thriller and character study. The 1974 film is not like most of the pathetic and mindless flicks of today. There are no superheroes, no CGI, no WOKE agenda, no gratuitous sex, nudity, and violence. The violence that does occur is presented as an off-stage event like in Greek tragedies.

See the called-out elements of its PG rating here: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0071360/parentalguide/?ref_=tt_ov_pg#certificates

The movie was shot using long lenses and camera positions on rooftops. You get the idea of watching at a distance and of surveillance cameras panning scenes.

Another reason to watch is that Gene Hackman was a great actor. The character study involving a Catholic man who is self-isolating and who hears and views others from a distance – Hackman’s Harry Caul makes the movie.

Another is to consider the consequences of hearsay or of unfounded information, of surveillance versus participation, and of perception versus reality. Can we really know someone, their thinking, and their situation from a distance, from what others would have us believe?

And, there is the matter of someone listening without our knowledge. Though made in 1974, the issues of privacy the movie presents are relevant regarding you and I being surveilled today. The analog technology shown in the film has been replaced with digital technology that gains access to our private electronic communications, as through wiretapping or the interception of e-mail or cell phone calls.

We live in the age of digital technology that includes emails, texts, smart phones, and social media. How does Harry’s addiction to technology that supports his habit of seeing and hearing others at distance and his voyeuristic predilections affect him?

~~~~~~

~~~~~

Finding God in Stories | Office Hours, Ep. 15

~~~~~

Scot Bertram talks with Clare Morell, fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and director of EPPC’s Technology and Human Flourishing Project, about the long-term effects of smartphone use on children and her new book The Tech Exit: A Practical Guide to Freeing Kids and Teens from Smartphones. And Benedict Whalen, associate professor of English at Hillsdale College, continues a series on the life and work of American writer Mark Twain. This week, he discusses The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Clare Morell Helps to Keep Kids Free from Screens – The Radio Free Hillsdale Hour – Omny.fm

~~~~~~