Somewhere in the Lost World of Love

February 4, 2024 Leave a comment

Love. Is it die-cut like the Valentine cards of grade school? Is it cliché like pop music? Is it a potion we constantly thirst for? Is it intoxication and under its influence we are not in our right minds? Is love passion? Sentimental? Carnal? Absolute? “What do any of us really know about love?”

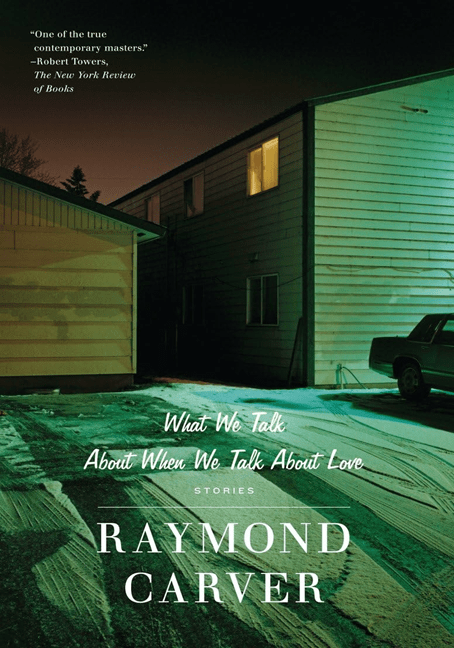

The last question is raised during a conversation between two couples. Their dialog and the juxtaposition of the couple’s ideas about love are found in Raymond Carver’s 1981 short story What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Carver has us listen in.

We learn from narrator Nick that he and his wife Laura are spending the afternoon at Mel and Terri’s home. Both couples live in Albuquerque, but as Nick says and the ‘love’ dialog relates, they “were all from somewhere else”.

Nick tells us that Mel McGinnis is a forty-five-year-old cardiologist who, before medical school, spent five years in seminary. Terri is his second wife. We later learn that Mel was married before to Majorie and has two children. His movements are usually precise when he hasn’t been drinking.

Terri, we learn, was previously in an abusive relationship with a guy named Ed. He would beat her and drag her around the room by her ankles, all the while professing his love for her.

Mel and Terri have been married for four years.

Nick tells us about Laura and their relationship: she’s a legal secretary who’s thirty-five and three years younger than he is. He says they’re in love, they like each other and enjoy each other’s company. “She’s easy to be with.” They’ve been married for eighteen months.

Beside the four adults, sunlight and gin figure in the story.

As the story begins, the four are sitting around a kitchen table. Sunlight fills the room. Gin and tonic water are being passed around. The subject of love comes up.

(I get the sense that the older couple have argued a lot about what love is and now want to air it all again in front of the younger couple. It seems they have things they want to get off their chest. Is that why the cheap gin is being passed around? Are Nick and Laura in place to be the arbiters of who’s right and who’s wrong?)

The heart doctor Mel, based on “the most important years of his life” in seminary, thinks that “real love was nothing less than spiritual love”. (This signals that love’s definition may not be solid.)

Terri believes that Ed, the man who tried to kill her, loved her. She asks “What do you do with love like that? Mel responds that Ed’s treatment could not be called love.

Terri then makes excuses for Ed’s behavior – “People are different”. She defends him – “he may have acted crazy. Okay. But he loved me.”

We begin to notice a growing tension between Mel and Terri. (There has been tension in their marriage about Ed and Marjorie before this.)

Mel relates that Ed threatened to kill him. Mel reaches for more gin and becomes antagonistic himself. He calls Terri a romantic for wanting brutal reminders of Ed’s love. Then he smiles at her hoping she won’t get mad. Terri responds to Mel, not with a rejection of his or of Ed’s behavior, but with what might have been her leave-the-door-open enabling response to Ed after one of his physical attacks: “Now he wants to make up.” Her past relationship reveals the continuous nature of Terri’s emotional deficit.

(Does Mel know how to land verbal blows on Terri like Ed did physically?)

Mel tries to soften the blow by calling Terri “honey” and by saying again that what Ed did wasn’t love. He then asks Nick and Laura what they think.

Nick says he doesn’t know the man or the situation to make a decision. Laura says the same and adds “who can judge anyone else’s situation?” Nick touches her hand and she smiles.

Nick picks up her “warm” hand, looks at the polished and manicured nails and then holds her hand. With this display of affection, Nick shows his love and respect for Laura, the opposite of the emotional and physical abuse Terri suffered at the hands of Ed.

Mel posits that his kind of love is absolute and nonviolent. (Then again, emotional abuse doesn’t kill or leave physical bruises.)

Terri and Mel describe Ed’s two attempts at suicide. Terri talks with sympathy for the guy. “Poor Ed” she says. Mel won’t have any of it: “He was dangerous.” Mel says they were constantly threatened by Ed. They lived like fugitives, he says. Mel bought a gun.

Terri stands by her illusion that Ed loved her – just not the same way that Mel loves her.

They go to relate that Ed’s first suicide attempt -drinking rat poison – was “bungled”. This puts him in the hospital. Ed recovers. The second attempt is a shot in the mouth in a hotel room. Mel and Terri fight over whether she will sit at his hospital bedside. She ends up there.

Mel reiterates that Ed was dangerous. Terri admits they were afraid of Ed. Mel wants nothing to do with Ed’s kind of love. Terri, on the other hand, reiterates that Ed loved her – in an odd way perhaps but he was willing to die for it. He does die.

Mel grabs another bottle of gin.

Laura says that she and Nick know what love is. She bumps Nick’s knee for his response. He makes a show of kissing Laura’s hand. The two bump knees under the table. Nick strokes Laura’s thigh.

Terri teases them, saying that things will be different after the honeymoon period of their relationship. Then, with a glass of gin in hand, she says “only kidding”. Mel opens a new bottle of gin and proposes a toast “to true love.”

The glow of the afternoon sun and of young love in the room makes them feel warm and playful, like kids up to something.

Matters-of-the-heart Mel wants to tell them “what real love is”. He goes on about what happens to the love between couples who break up. After all, he once loved his ex-wife, Marjorie, and Terri once loved Ed. Nick and Laura were also both married to other people before they met each other.

He pours himself more gin and wipes the “love is” slate clean with “What do any of us really know about love?” He – the gin Mel – talks about physical love, attraction, carnal love, sentimental love, and memory of past love. Terri wonders if Mel is drunk. Mel says he’s just talking. Laura tries to cheer Mel by saying she and Nick love him. Mel responds saying he loves them too. He picks up his glass of gin.

Mel now gets around to his example of love, an example that he says should shame anyone who thinks they know what they are talking about when they talk about love. Terri asks him to not talk drunk. (Is Mel, focused only on himself and his gin, becoming a slurring, stammering and cursing drunk?) He tells her to shut up.

Mel begins his story of an old couple in a major car wreck brought on by a kid. Terri looks over at Nick and Laura for their reaction. Nick thinks Terri looks anxious. Mel hands the bottle of gin around the table.

Mel was on call that night. He details the extensive wounds. The couple is barely alive. After saying that seat belts saved the lives of the couple, he then makes a joke of it. Terri responds affirmatively to Mel and they kiss.

Mel goes on about the old couple. Despite their serious injuries, he says, they had “incredible reserves” – they had a 50/50 chance of making it.

Mel wants everyone to drink up the cheap gin and then go to dinner. He talks about a place he knows. Terri says they haven’t eaten there yet. The heart doctor’s coherence dissipates with each drink.

He says he likes food and that he’d be a chef if he had to do things all over again. Then he says he wants to come back in another life as a medieval knight. Knights, he says, were safe in armor and they had their ladies. As he talks, Mel uses the word “vessels”. Terri corrects him with “vassals”. Mel dismisses her correction with some profanity and false modesty.

Nick counters the heart doctors fantasy by saying that knights could suffer a heart attack in the hot armor and they could fall of a horse and not get back up because it is heavy.

Mel responds to Nick and Terri, acknowledging it would be terrible to be a knight, that some “vassal” would spear him in the name of love. More profanity. More gin.

Laura wants Mel to return to old couple story. The sunlight in the room is thinning. (And so is “love’s” illumination.)

Terri gets on Mel’s nerves with something she said jokingly. Mel hits on Laura saying he could easily fall in love with her if Terri and Nick weren’t in the picture. He’d carry her off knight-like. (Terri and Nick, of course, are sitting right there.)

Mel, with more vulgarity, finally returns to his anecdote. The old couple are covered head to toe in casts and bandages with little eye, nose and mouth holes. The husband is depressed, but not about his extensive injuries. He’s depressed because he cannot see his wife through his little eye holes. Mel is clearly blown away by this kind of love. He asks the other three if they see what he’s talking about. They just stare at him.

Sunlight is leaving the room. Nick acknowledges that they were all “a little drunk”.

Mel wants everyone to finish off the gin and then go eat. Terri says he’s depressed, needs a pill. Mel wants to call his kids, who live with his ex-wife and her new boyfriend. Teri cautions Mel about taking to Marjorie – it’ll make him more depressed.

Terris says that Marjorie, because she isn’t remarried, is bankrupting them. Mel, who says he once loved Marjorie, fantasizes about Majorie dying after being stung by a swarm of bees, as she’s allergic to bees. Mel then shows with his hands on Terri’s neck how it would happen to “vicious” Marjorie.

Mel decides against phoning his children and mentions about going out to eat again. Nick is OK with eating or drinking more. Laura is hungry. Terri mentions putting out cheese and crackers put she never gets up to do this. Mel spills his glass of gin on the table – “Gin’s gone”. Terri wonders what’s next.

As the story ends, daylight (illumination) is gone from the kitchen. The four are ‘in the dark’ about what love really is. The conversation is also gone after Mel’s futile attempts to talk about love in any satisfying way and the inability of two characters to move on from the past and with two characters wondering what’s next.

The only sound Nick hears is the sound of human hearts beating (somewhere in the Lost World of Love).

~~~~

This story, though not of “Christian” genre, certainly would resonate with many readers. Do you relate to anyone in the story?

Terri understood Ed’s abusive and suicidal behavior as him being passionate about love. Mel, the heart doctor and would-be knight, showed himself idealistic and ignorant about the realities of the ‘heart’ and not loving towards Terri. Nick and Laura revealed the affection and passion of the heady first days of romance love. The old couple possessed an enduring love for each other after many years of marriage.

Why would I, as a Christian, gravitate to a ‘worldly’ author like Raymond Carver, especially when his stories are filled with alcohol? One reason is that I recognize myself in many of his stories. I see elements of myself at various stages of my life in each of the characters above. I could pretend to see myself otherwise, as I think some Christians do.

Another reason is that Carver writes about working class people. He doesn’t write down to people. His writes stories of domestic American life with its passions, fears, foibles, and fantasies. He writes with realism about human nature, revealing the old self that I must recognize in myself to put away.

I find his writing sobering, as in his story Where I’m Calling From.

~~~~~

RARE: Raymond Carver Reads “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” (youtube.com)

~~~~~

Men need sex. And it’s their wives’ job to give it to them—unconditionally, whenever they want it, or these husbands will come under Satanic attack.

Stunningly, that’s the message contained in many Christian marriage books. Yet, research shows that instead of increasing intimacy in marriages, messages like these are promoting abuse.

In this edition of The Roys Report, featuring a talk from our recent Restore Conference, author Sheila Wray Gregoire provides eye-opening insights based on her and her team’s extensive research on evangelicalism and sex.

How Christian Teachings on Sex Enable Abuse | The Roys Report (julieroys.com)