Faith in Dialog with Einstein

September 17, 2023 Leave a comment

Can’t see the forest from the trees? Can’t see anything but a thicket of theology? Maybe it’s time for stepping back, reassessing, and gaining a broader perspective . . . for the future of your faith.

In 1944 Robert Thornton, a young African American philosopher of science, wrote to Albert Einstein. Thorton had just finished his Ph.D. and was about to begin a new job teaching physics at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez. Thornton wanted to introduce “as much of the philosophy of science as possible” [the “forest”] into the modern physics course that he was to teach the following spring. He was hoping for support. Einstein offered this reply:

“I fully agree with you about the significance and educational value of methodology as well as history and philosophy of science. So many people today—and even professional scientists—seem to me like somebody who has seen thousands of trees but has never seen a forest. A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is—in my opinion—the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth. “(Einstein to Thornton, 7 December 1944, EA 61–574)[i] (Emphasis mine.)

Writing in A Theory of Everything (That Matters): A Short Guide to Einstein, Relativity and the Future of Faith,[ii] the former atheist and currently Oxford’s Emeritus Professor of Science and Religion Alister McGrath[iii] writes that “For Einstein, it was important to develop a unified Weltbild – a coherent and comprehensive way of seeing our world – that would allow individual trees to be seen and appreciated for what they were while at the same time seeing them as part of something greater.[iv](p93).

“A coherent and comprehensive way of seeing our world” is the point of a Theory of Everything (That Matters):

“One of the central themes of this volume is the need to reflect on Einstein’s belief that it was possible to hold together – if not weave together into a coherent unity – his views on science, ethics, politics and religion.”[v] (p89)

Einstein sought a unified theory of everything. That makes him an “excellent dialogue partner”[vi], per McGrath. Without naming a contentious issue but implying a context of Christianity vs. science, the professor asks “What might a Christian learn from Einstein? How does Einstein inform and engage with a Christian ‘big picture’ of the world?”

To help us understand Einstein’s way of thinking, the “short guide’ places Einstein in history (WWI, WWII, a Jew in Nazi Germany, Atomic weapons) and in line with a science great- Issac Newton.

Newton had published (in 1687) his Principia “which set out his three laws of motion, the modern concepts of force and mass, and the new and deeply counterintuitive concept of universal gravitation.” (p31) Newton had a hand in developing differential and integral calculus and discovered that white light is made up of colored rays. From one genius to the next.

1905, Albert Einstein worked as a clerk in a Swiss patent office. His job was not challenging so he began thinking about physics problems posed in physics journals!

We learn about the Einstein’s brilliant theoretical account of the photelectric effect and the nature of light which challenged the classical notions of the nature of light.

“Although Einstein went on to gain worldwide fame after the end of the Great war for his general theory of relativity, a Nobel prize in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, the roots of that latter fame lay in a series of four groundbreaking articles in he published in the leading journal Annel der Physik (Annals of Physics) in 1905.”[vii] (33)

McGrath provides simplified explanations of Einsetin’s revolutionary theories, including the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, special relativity (developed using thought experiments), the equivalence of matter and energy (e=mc²), and the general theory of relativity (converting gravitational physics into the geometry of space-time, space-time being an elastic structure which is deformed by the presence, in its midst, of mass-energy).

Beside noting Einstein’s outside-the-box scientific achievements, McGrath also has the reader see that Einstein cared about greater issues. Here, McGrath quotes Einstein:

“By painful experience we have learnt that rational thinking does not suffice to solve problems of our social life. Penetrating research and keen scientific work have often had tragic implications for mankind, producing, on the one hand, inventions which liberated man from exhausting physical labor . . . but on the other hand . . . creating the means for his own mass destruction.”[viii]

Einstein, as McGrath explains, was not a religious man in the sense of religious ritual. He was aware of Jewish texts but he was not a practicing Jew. And though Einstein did not believe in a personal God, he did not shut out a belief in a ‘superior mind’ behind the universe. This belief came out the awe and wonder he experienced in discerning the complexity and coherence of the universe.

McGrath remarks that “Einstein’s approach was to treat science and religion as two distinct aspects of our attitude to our universe. . ..

“His core aim was to consider the relationship of two different realms or modalities of human thought: science (facts) and religion (values).”[ix] (P123) He quotes Einstein: “Science can only ascertain what is, but not what should be.”[x] (p125) McGrath goes on to say . . .

“Tensions arise, Einstein suggests, when religion intervenes ‘into the sphere of science’ – for example, in treating the Bible as a scientific text – or when science attempts to establish human ‘values and ends’.”[xi]

Professor McGrath, with A Theory of Everything (That Matters), would have us consider that there are Two Books revealing “Divinity”- Christianity’s scripture and natural sciences. The “Two Books” metaphor, as McGrath notes[xii], emerged during the Renaissance when the natural sciences took off, with the aid of telescopes and microscopes and experimentation, and replaced the church-controlled narrative about nature.

Encouraging a dialog with Einstein’s coherent and comprehensive way of seeing our world, Professor McGrath would have us, I believe, begin to think beyond what we think we know and what we swear to and use to accuse others of being deceived (see below).

We live in a scientific universe, not just a theological universe. With that in mind, I hope that you will read this book. I recommend the book for homeschoolers. The science is written for laymen. A thinking-outside-the-box philosophy of science like Einstein’s is good for one’s education and faith. Thinking that includes both scripture and natural science will enrich your faith. And who knows what you may discover as you venture beyond the thicket!

And why was the tree stumped? Because it couldn’t get to the root of the problem.

I hope you will listen to the podcast.

This podcast discusses two of Alister McGrath’s s more recent books: A Theory of Everything (that Matters) and Narrative Apologetics. The conversation ranges from talking about Einstein’s religious beliefs and how they open a door for exploring the relationship between science and theology, to the importance of storytelling for Christian Apologetics.

28. Alister McGrath | Journey of Science, Story of Faith | Language of God (biologos.org)

~~~~~

During the podcast, Alister mentions that he had received a microscope as a child.

When I was about ten-years-old, my father gave me a microscope for a Christmas present. I was delighted. All my other childhood gifts had been, shall I say, for kids. The microscope came with specimen slides, so I could start my discoveries that day.

Except for that one wonderous time, I was not raised to think about science. And nature, where I had spent a lot of time as a child, was not something you thought about except for the weather. It was just there.

I was raised to think of everything in terms of scripture. Nature was taught and preached as Psalm 19, six literal days of material creation, a worldwide flood, and as a place to escape and be raptured from, as in “this world is not my home I’m just a-passing through . . .” This became for me a fragmentary view of things, especially as I engaged others with my scripted view of the universe. To be honest, most of my church experience has been intellectually stifling.

So, I began to read books about physics, astrophysics, genomics, and other science texts. I took an interest in astronomy and ornithology, the study of birds. (Astronomers stay up very late and bird song seems to happen early in the morning, so I have to change my ways.)

I also read and researched the contexts of OT and NT scripture using the works of scholars like John Walton, Richard Bauckham, N.T. Wright and others. I wanted to grow intellectually and engage my imagination. And that is why I found McGrath’s book so interesting. I wanted to know more than what had been handed to me.

I also starting memorizing whole passages of scripture, as memorizing individual verses is taking them out of context. You see the latter often mis-used on social media. Memorizing whole passages of scripture – I’ve memorized four Psalms and five-and-a-half chapters of the Gospel of Mark – puts me into the context. With the Psalms, I am the one reflecting and reminding myself of God’s sovereignty and of His loving care for creation. With the Gospel according to Mark, I feel like I am there. In Mark 6:37, for example, when Jesus says to me, “You give them something to eat” what do I do?

I thought that there was only thing I had in common with a genius like Einstein – what Einstein stated about himself: “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.” Then I read A Theory of Everything (That Matters): A Short Guide to Einstein, Relativity and the Future of Faith.

Each of us is born into a passed-down way of understanding the world that later informs our judgements. Einstein’s cultivation of a philosophical habit of mind, his questioning attitude, provided his independence of judgement. That is something I share with Einstein.

Speaking of in terms of scientific advancement, Einstein writes about challenging a handed-down way of thinking in his “1916 memorial note for Ernst Mach, a physicist and philosopher to whom Einstein owed a special debt”:

“Concepts that have proven useful in ordering things easily achieve such an authority over us that we forget their earthly origins and accept them as unalterable givens. Thus they come to be stamped as “necessities of thought,” “a priori givens,” etc. The path of scientific advance is often made impassable for a long time through such errors. For that reason, it is by no means an idle game if we become practiced in analyzing the long commonplace concepts and exhibiting those circumstances upon which their justification and usefulness depend, how they have grown up, individually, out of the givens of experience. By this means, their all-too-great authority will be broken. They will be removed if they cannot be properly legitimated, corrected if their correlation with given things be far too superfluous, replaced by others if a new system can be established that we prefer for whatever reason. (Einstein 1916, 102”)[xiii] (Emphasis mine.)

“What might a Christian learn from Einstein? How does Einstein inform and engage with a Christian ‘big picture’ of the world?”

~~~~~

“Abandon the urge to simplify everything, to look for formulas and easy answers, and to begin to think multidimensionally, to glory in the mystery and paradoxes of life, not to be dismayed by the multitude of causes and consequences that are inherent in each experience — to appreciate the fact that life is complex.”

― M. Scott Peck, (1936–2005), American psychiatrist and best-selling author

[i] Letter to Robert Thornton, dated 7 December 1944. Einstein Archive, Reel 6-574

[ii] A Theory of Everything (That Matters): A Short Guide to Einstein, Relativity and the Future of Faith,

[iii] Professor Alister McGrath | Faculty of Theology and Religion (ox.ac.uk)

[iv] Ibid 93

[v] Ibid 89

[vi] Ibid 135

[vii] Ibid 33

[viii] Ibid 63

[ix] Ibid 123

[x] Ibid 125

[xi] Ibid 124

[xii] Ibid 141

[xiii] Einstein’s Philosophy of Science (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

~~~~~

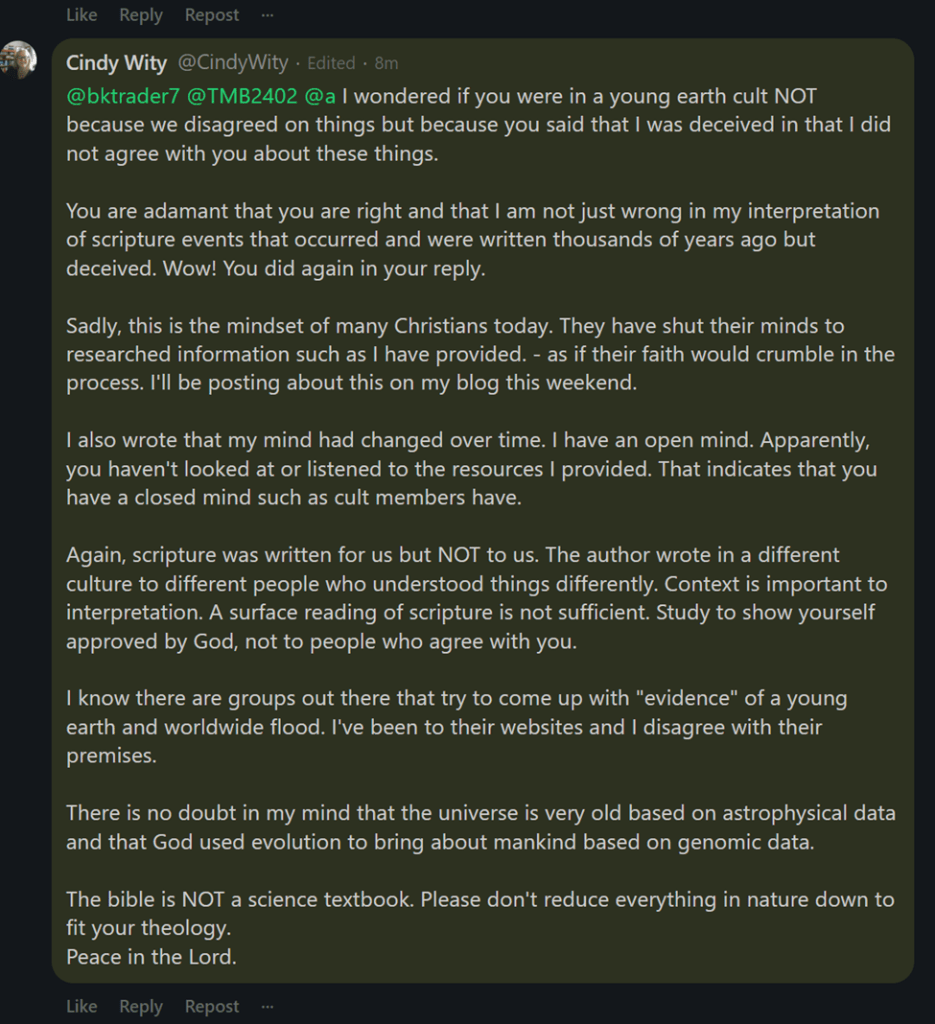

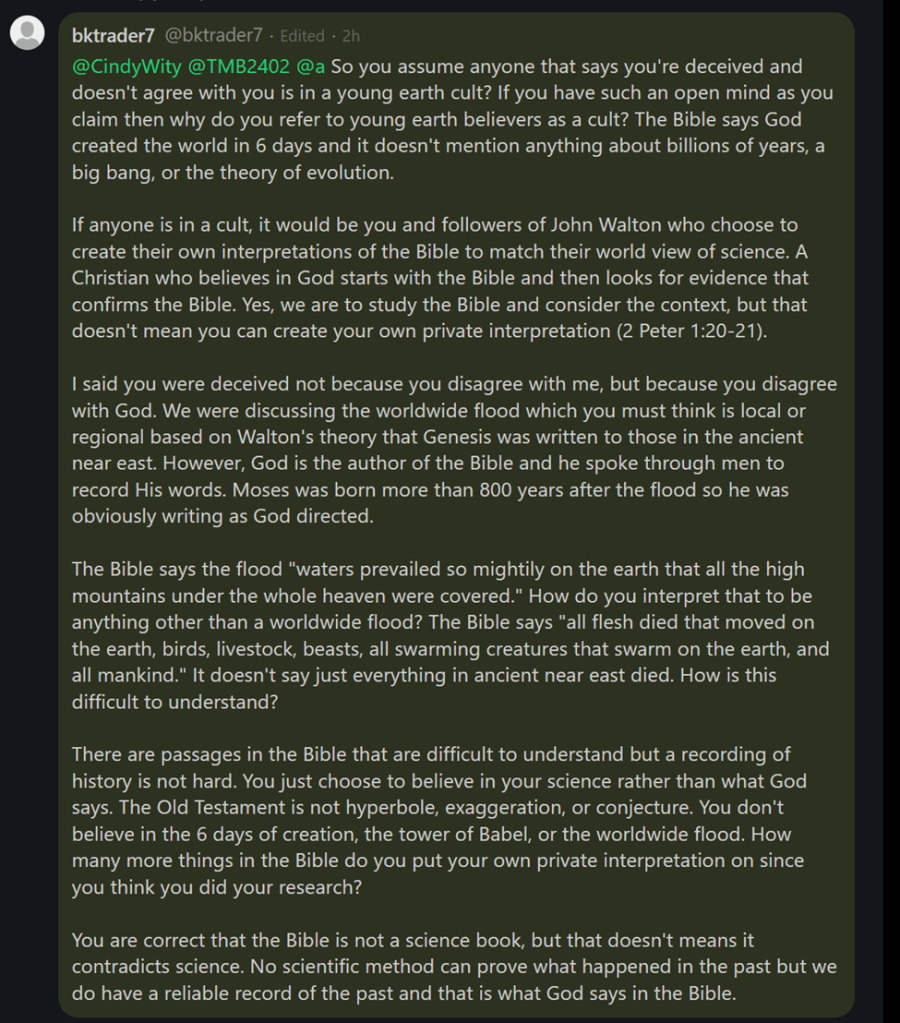

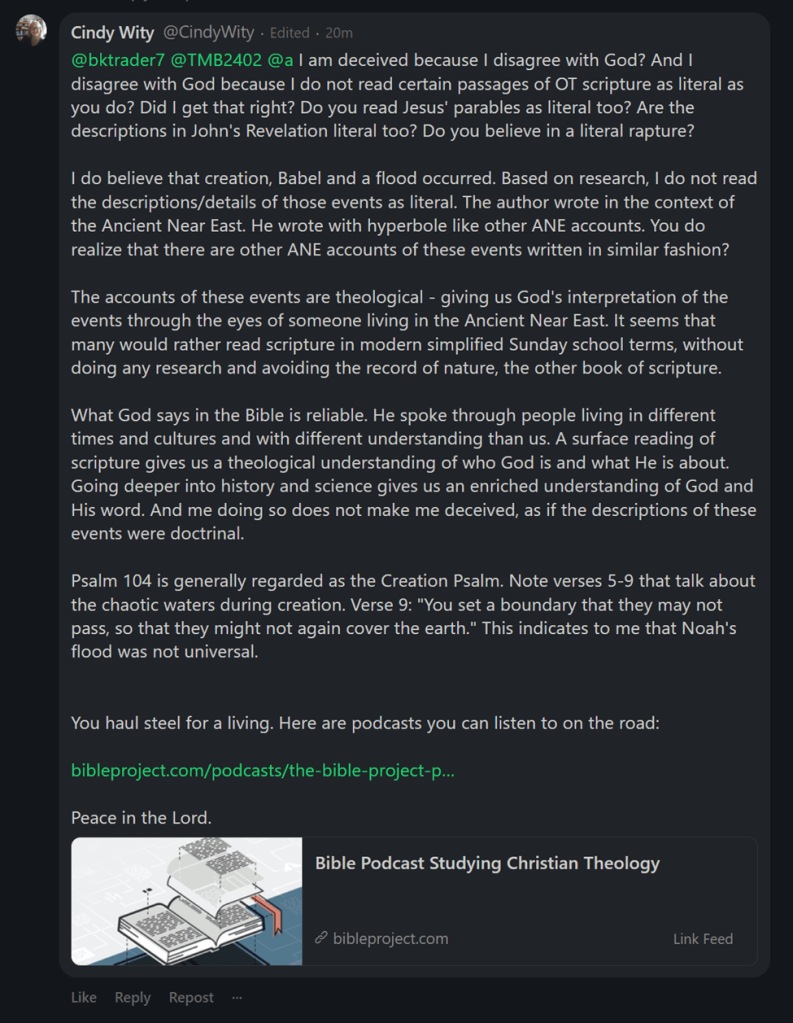

As I finished reading the book and started writing this post, I became engaged in a conversation on social media. My intent was to propose a different perspective than what I would call a locked-in “fundamentalist literal” perspective. Below are the screen captures.

Andrew Torba, CEO of GAB, posted the initial comment of the Tower of Babel below. Note the number “likes” for what he posted. Some of the replies were from those who thought it more Christian nonsense. I stepped in with my comment and then someone began commenting back. Here’s the dialog:

Links I provided:

John Walton – “Lost World of the Flood” – YouTube

John Walton: The Meaning of the Tower of Babel

Bible Podcast Studying Christian Theology (bibleproject.com)