Now Cracks a Noble Heart

August 24, 2025 Leave a comment

Ten years ago, a priest took me aside and asked how I was doing. After sharing general things, I confided that I have a deep well of pain inside me and that if any of it was brought to the surface, I don’t know what would happen. A recent reading of Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark has me thinking that this was true for Hamlet.

My drama has not been one of ghosts, murder mystery, revenge, poison, war, love, suicide, pirates, and fencing. Not exactly. Yet, like Hamlet, I have dealt with the unresolved past, the uncertain present, the Machiavellian within and without, and loss (Shakespeare’s eleven-year-old son Hamnet died a few years before Hamlet was published.). Dueling deliberations about how to proceed with matters of heaven and earth had my disposition of two minds.

Working through internal and external out-of-whack things, I reacted variously: deliberative, antic, witty, acerbic, warmly caring and steely cold. And the back-and-forth between guilt, perception, and reality had my sick soul grappling with the weight of my actions and their repercussions. Foiled attempts at living a serious and noble life resulted in a profound source of pain.

“Life is pain, highness. Anyone who says differently is selling something.” from William Goldman’s The Princess Bride.

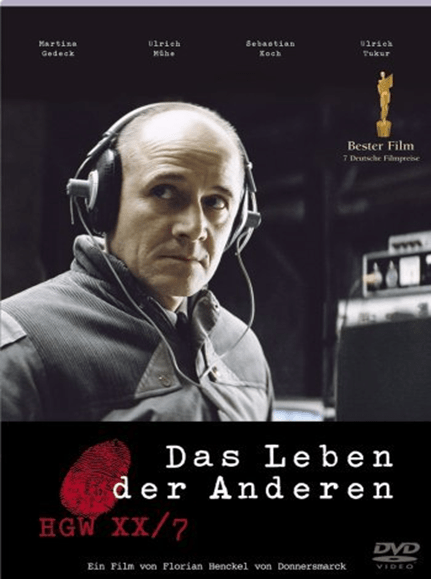

Hamlet, constantly monitored, was deemed uncontrollable and too dangerous to be around. The king tried to exile him. Likewise, there are those who watch me from a distance and keep me at a distance as too unsettling to be around, exiled to their version of purgatory. But after reading Hamlet, I take comfort in this: Man is too complex for any final judgement here on earth.

Below, notes made while reading Hamlet a second and third time and retelling the tragedy in my own words. It’s been my experience that rereading previous works as you get older provides new insights thereby expanding temporal bandwidth. Rereading Hamlet reset my Christian imagination.

This personal exercise, in no wise exhaustive of the depths of Hamlet, was done to understand the prince, the play and the “Who’s there?” persona of my own drama.

Though there is plenty of wit, there are no snappy answers to the existential issues raised in the play. In fact, there is a lot of ambiguity and a lot questions, layers of them. The word “question” is used fifteen times. Hamlet himself is a question mark.

Anyway, that is my prologue to Hamlet.

~~~

You’re a serious young man in your late twenties. You are intellectually curious. You love a good drama. You love to act. You think you’ve got a handle on things. You’re in a good place. But then the order of things is radically altered and you enter uncharted territory. You soon find yourself in a black hole of “to-be-or-not-to-be” despair. You have a lot to come to terms with as heir to the throne of Denmark.

Hamlet, a student of religious and philosophical inquiry at the University of Wittenberg, had to grapple with the major religious reform of medieval Catholic theology. October of 1517, a professor of moral theology at the university posted 95 Theses on a local church. Martin Luther challenged papal policy and stressed the inward nature of the Christian faith over the overt money-laundering indulgences that fed the rich papacy in Rome.

Indulgences were based on a belief in purgatory, a prison of souls in the next life where one could supposedly continue to cancel the accumulated debt of one’s sins. Dante’s 14th century poem “Purgatorio” pictured purgatory as a place of unresolved sin, spiritual anguish, and the quest for redemption. Then, in the late Middle Ages, thinking about the after-life was radically altered. English Protestants rejected the Catholic notion of purgatory.

Beyond theology, the Catholic Church’s traditional geocentric model of the universe was also being rejected for a heliocentric cosmological model. Wittenberg was the center for Copernican cosmology. (See the article below regarding Hamlet as an allegory for the competition between the cosmological models.)

Back in Denmark, potential war with Norway was on the horizon. The Norwegian crown prince’s father was killed in a duel by Hamlet’s father, King Hamlet. Fortinbras was determined to avenge his slain father.

In this setting, Hamlet returns to Denmark for the funeral of his father, King Hamlet. In court he wears black to mourn. His demeanor is somber.

So much for backstory. The unresolved takes over from here.

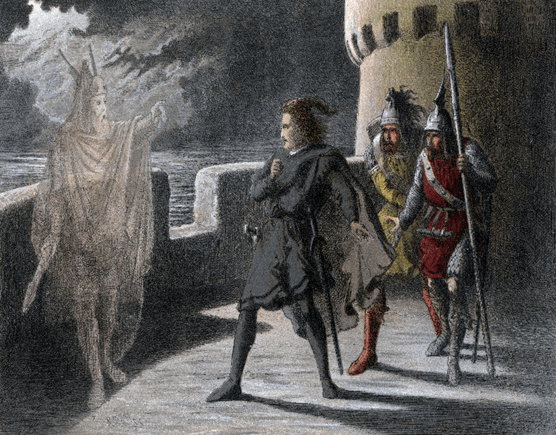

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark opens on the cold and windy ramparts of the royal palace located in the coastal city of Elsinore. As sentinels keep all-night watch for an approaching army, a ghost appears instead. The apparition has shown up a couple of times at the same time of night – the changing of the guard. Two sentinels invite Hamlet’s Wittenberg school buddy, Horatio, to see for himself. He had questioned their report.

The ghost looks like Hamlet’s dead warrior father. The figure seems to only want to speak to his son. So, Horatio decides to bring Hamlet to the ramparts to check it out. But first, Hamlet heads to court.

~~

A1S2: King Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle, sends two courtiers to Norway hoping to persuade Fortinbras from attacking Denmark. He then addresses Laertes, the son of the Lord Chamberlain Polonius, and his desire to return to school in France. The king then turns to the gloomy Hamlet: “How is it that the clouds still hang over you?”

Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, now married to Claudius, chides Hamlet. She wants him to get rid of the black clothes and to get on with life, saying that death is an everyday event. She wants to know why death “seems” so important to Hamlet.

Hamlet rejects his mother’s understanding of his grief. He wants her to know that the magnitude of his internal grief is greater than what his black clothes and brooding attitude portray.

Claudius, cold and conniving, chimes in. He downplays death as just what happens in the family tree. He then scolds his nephew by saying that he is overdoing his grief and is not acting manly that way. He wants Hamlet to see him as his new father.

Hamlet gets a sense of the dysfunction, of how out of whack things are, in Denmark. He sees that Claudius and his mother are quite a warped pair! He wants to return to an emotionally healthy place -Wittenberg. The King and Queen encourage him to stay in Denmark. At his mother’s request, Hamlet agrees to do so.

(Another level of abnormal, though never mentioned: Claudius has usurped the throne; Hamlet is the rightful heir.)

Claudius and Gertrude leave court. Hamlet sticks around to lament out loud to himself those feelings of anguish that Claudius and Gertrude could not or would not fathom. His return to Denmark has brought him to a place of suicidal despair:

O that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!

Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d

His canon ’gainst self-slaughter. O God! O God!

How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on’t! Oh fie! ’tis an unweeded garden

That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.

Regarding the moral bankruptcy of his mother – she was quick to marry Claudius after her husband’s death – he says “Frailty, thy name is woman!”

Two sentinels and Horatio enter. They describe what they saw on the ramparts: an apparition that looked very much like Hamlet’s dead father in full armor. Hamlet agrees to go see the ghost that night with him. Hamlet, alone, says to himself

My father’s spirit in arms! All is not well;

I doubt some foul play: would the night were come!

Till then sit still, my soul: foul deeds will rise,

Though all the earth o’erwhelm them, to men’s eyes

~~

A1S3: Elsewhere, Laertes, before heading off to France, counsels his sister Ophelia not to fall in love with Hamlet, to consider his prime devotion to his royal responsibilities and his hot bloodedness.

Polonius, their father, enters the scene. He gives fatherly advice to Laertesabout how to conduct himself while at school in France. Educated but not a deep thinker, Polonius repeats common proverbs he learned by rote. These include ‘don’t say what you are thinking, don’t be quick to act, be friendly but don’t overdo it, don’t pick fights’ and “Neither a borrower nor a lender be.”

Laertes takes off. Polonius turns to his daughter Ophelia to give her fatherly advice about Hamlet. He cautions her to not believe his vows of love and to guard her affections. This instruction, in political terms, seems odd to me. Hamlet is the rightful heir to the Danish throne. Ophelia could marry Hamlet and Polonius would be in a good position.

~~

A1S4: That night Hamlet waits with Horatio and Marcellus for the ghost to appear. When it does, it motions for Hamlet to come with it. Both the sentinel Marcellus and Horatio are concerned about the harrowing encounter – Hamlet going off with the ghost to hear what it says. Hamlet considers it his destiny to follow the ghost and resolves to do so.

Horatio is uneasy about the appearance of the Ghost and the omen it might represent. Marcellus, a sentinel trained at keeping watch on the castle battlements, senses that something is off. He says, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.” A supposed ghost of the late king doesn’t just appear if all is right in the kingdom. Horatio responds to Marcellus, “Heaven will direct it.” They follow Hamlet.

~~

A1S5: The ghost-father, saying he will soon return to purgatory, charges Hamlet to wreak vengeance on his uncle, the one who murdered him before he was able to repent of his sins and receive last rites. He describes how Claudius murdered him and how he seduced Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, with words and gifts. He tells Hamlet to spare his mother Gertrude, to leave her to God to judge. Should Hamlet also do this with Claudius and not get involved in murder?

Hamlet vows to remember his father. The high-minded and contemplative Hamlet is directed to get his hands dirty. Will the unresolved past and the rottenness in Denmark taint his thinking, his morality, his actions?

Horatio and Marcellus come up and want to know what transpired with the ghost. Hamlet gives an oblique answer. Horatio presses and Hamlet won’t say what he was told. Instead, he asks his these two to swear to not say anything about what they saw or heard. The ghost, moving around behind the scenes, shouts “Swear!” four times to Horatio and Marcellus as Hamlet tells them to not to disclose what has happened and to not react not matter how strangely he reacts in the future.

Hamlet then tells the ghost to rest. No one will talk. And tells Marcellus and Horatio to shush up when the three go back to court. And then he gives his perspective on the whole mess and having to deal with it:

The time is out of joint. O cursed spite,

That ever I was born to set it right.

Nay, come, let’s go together.

~~~

A2S1: Elsewhere, Polonius sends his servant with money for his son Laertes who is studying music in France. He tells Reynaldo to check around in a back-handed way (to spy) to get impressions of his son. Is Laertes studying or is he sowing wild oats?

Ophelia shows up in a frazzled state. She tells her father that Hamlet came to her behaving strangely. Polonius attributes Hamlet’s behavior to love madness. He asks Ophelia if she has led him on or pushed him away. She says she has refused his entreaties. Polonius, who loves to give advice, wants to advise Claudius of Hamlet’s craziness.

~~

A2S2: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, school chums of Hamlet, arrive in court. Claudius and Gertrude want both of them to hang around (spy on) Hamlet to find out what’s behind his crazy behavior and perhaps, cheer him up. When they leave court to find Hamlet, Polonius enters court. He wants to tell the king his theory of Hamlet’s madness, but first he wants the king to listen to the report of the Norwegian ambassadors who just arrived. He goes to retrieve the Norwegians.

While gone, Claudius comments to Gertrude that he is eager to hear Polonius’ proposed theory. Gertrude responds by saying Hamlet’s madness is not doubt tied to his father’s death and their quick marriage.

The two ambassadors enter and explain to Claudius that their king has deterred Fortinbras from attacking Denmark. They leave court.

Then the wordy Polonius gets on with his report about Hamlet’s craziness in a long-winded and redundant fashion. Gertrude can’t handle his bloviating and tells him to get to the point: “More matter, with less art.”

Polonius presents Hamlet’s love letter to his daughter Ophelia. He claims that this shows that Hamlet is madly in love and that Ophelia’s rejection of him has made him melancholy and lose his mind.

Claudius wants to know if this is true. Polonius says they can discover whether Hamlet really has gone mad from when he is set up to be alone with Ophelia. He and king will hide and see what happens. Claudius agrees to go along with the scheme.

Hamlet arrives. Polonius tells the king and queen to leave so he can deal with him. The verbose Polonius engages Hamlet in a conversation. Hamlet, in feigned-madness mode, responds to Polonius with witty nonsense. When Hamlet answers off-subject but with wise insights, Polonius takes note and says, “There is a method to his madness.”

Two of Hamlet’s friends from Wittenberg. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, arrive and Polonius takes off. Hamlet is pleased to see his friends. The two share some bawdy banter with their friend Hamlet. And then Hamlet waxes philosophical. He wants to know why the two of them are back in Denmark which he calls a prison. They disagree with his assessment. Hamlet replies “Why, then, tis none to you, for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so. To me it is a prison.”

The two friends ascribe Hamlet’s melancholy as disappointed ambition that wants more. Hamlet ascribes it to bad dreams. He then wants know why they showed up. After some coaxing, they admit they were sent for.

Hamlet explains their being summoned is to cheer him up. But he says that he’s not interested in anything. The world holds nothing for him. But then Rosencrantz wonders if Hamlet would be interested in the drama company coming to entertain him.

Hamlet wants to know all about the troupe, the one that he so enjoyed, and the state of the theater. Trumpets blow announcing the arrival of the actors. Hamlet welcomes them and tells them that his “uncle-father and aunt-mother” have the wrong idea about his madness- it comes and goes at will.

Polonius enters and the players follow him into the room. Hamlet welcomes them and asks one of them to give him a speech about avenging a father’s death. He recites some of the lines himself and then has a player take over. The verbose Polonius comments that the speech is too long and Hamlet replies him with mocking wit.

Hamlet is impressed by the actor’s emotionally charged speech. He tells Polonoius to take them to their rooms and treat them well. As the players leave, he asks if they can perform The Murder of Gonzago the next night. The answer is yes. Hamlet tells them that he will write some additional lines into the play.

Polonius, the actors, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern leave. Hamlet is alone with his thoughts.

Having just seen the raw emotion of an actor reciting lines about people who are of no consequence to him, Hamlet belittles himself for not being able to generate any passion to avenge his own father. He scolds himself as one who mopes around and is cowardly. He calls himself an ass. He has been given motive to act and avenge the death of his father and he does not have his act together. But this reflection gives him an idea.

Having just experienced the effect of the actor’s intensity on his own conscience, he knows of others, too, who have had their conscience pricked when art imitates life. Having the acting troupe produce a play that mirrors the murder of his father may just reveal Claudius’s guilt and his own catharsis.

Hamlet, who may have studied Aristotle’s Poetics while at Wittenberg, comes across like a self-styled critic and dramatist of the theater. He knows how he wants the actors to perform and edits and adds to the script, for . . .

The play’s the thing

Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King.

~~~

A3S1: Claudius, Gertrude, Polonius, Ophelia, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern enter court. Claudius questions Hamlet’s two friends about Hamlet’s disposition. They say he’s responsive but difficult to read. They also say that he is excited about a play being put on by a recently arrived troupe. Hamlet wants the king and queen to attend. Polonius, unaware of Hamlet’s Mousetrap, agrees with this invitation. He has a trap of his own.

Polonius, along with Claudius, wants to find out if unrequited love is the reason Hamlet is beside himself. Ophelia, Hamlet’s love interest, is instructed by her father Polonius to walk around with a prayer book, look spiritual, and wait for Hamlet. He adds that people often do this – act devoted to God – to mask their bad deeds. Claudius hears this. To himself, he admits that these words have produced a sharp pang of guilt within.

When they hear Hamlet coming, Claudius and Polonius hide to spy on him. Hamlet enters and begins to speak only to himself of things that make his life, this mortal coil, tedious, irritating, and unbearable. His aversion to being contemplates relieving himself of the messiness of life by suicide:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die—to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d.

Hamlet ponders the well-known tribulations of life and then counters that with the “undiscovered country from whose bourn no travel returns.” From the later he reckons that fear of the unknowns of death, which would include purgatory, makes us all cowards. And too much back-and-forth thinking, he decides, makes one less daring and of no use when things need to get done.

Hamlet then comes across Ophelia reading her prayer book. He greets her and then goes on to speak to her in a cold-hearted way. Has he, because of the moral bankruptcy of his mother, decided to not put any trust in a woman?

He tells her that he never loved her. He bitterly denounces humankind, marriage, and the deceitfulness of beauty and women. He tells her to go to a convent. When he leaves, Ophelia laments the change that has come over the once noble Hamlet.

His intense words with Ophelia suggest that Hamlet has turned from acting mad to acting with madness.

Claudius and Polonius come out of hiding. Claudius is now aware that Hamlet’s behavior is not related to Ophelia but is likely related to something more out-of-control dangerous. He wants to send Hamlet to England (exile him) in hopes of changing his disposition. Is England to be Hamlet’s purgatory?

~~

A3S2: Later, Hamlet is with the actors, advising them how to speak their parts in the play that night. When Polonius, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern show up Hamlet confirms that the king and queen will be attending. They confirm this and leave to help the actors prepare. Horatio enters.

Hamlet expresses his high regard for Horatio and praises Horatio’s self-control. He then asks him to watch his uncle carefully during the play. Claudius’ response will determine whether the ghost was speaking the truth or just being a damned ghost. Hamlet will keep an eye on Claudius too.

Trumpets announce Claudius, Gertrude, Polonius, Ophelia, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. As they take their seats, Hamlet responds with nonsense to Claudius and Polonius. He chooses not to seat next to his mother. He sits with Ophelia and speaks to her in a mischievous way. Ophelia comments that Hamlet seems to be in a good mood tonight.

Hamlet retorts that God is the best comic. And, revealing with spite what truly galls him, he says why shouldn’t he be happy when his mother is so happy just a short time after his father has died. He should get rid of his black clothes and get some new snappy outfit.

Trumpets play and the pantomime show begins as a summary of the spoken drama to follow. The players mime the murder of the king by the same means as Hamlet’s father was murdered and then the queen accepting the murder’s advances.

Ophelia wants to know what it means. Hamlet impishly tells Ophelia “It means mischief.”.

The Prologue speaker enters to introduce the play. Puckish Hamlet tells Ophelia that this guy will explain everything as actors can’t keep things to themselves.

The Prologue actor speaks only three short lines, entreating the audience to watch the tragedy.

Hamlet asks whether that was the prologue or the inscription on a wedding ring? Ophelia replies “Tis brief, my lord.” And Hamlet comes back “As a woman’s love.”

The play begins with actors playing king and queen. They reenact the Murder of Gonzago. The play closely parallels the circumstances of the murder of Hamlet’s father, the king, as told by the ghost and the aftermath of the queen marrying the murderer. In this play the nephew, not the uncle, is the murderer.

The play begins with the king, who is nearing death, recounting his thirty years of marriage to the queen. He says that after he is gone, perhaps she will remarry. The queen protests and speaks of her undying love for him even after his death. If she did remarry, she vows, all of life should turn against her.

Hamlet to Ophelia: “If she should break it now!” – a pointed reference directed at Hamlet’s mother for her being so quick to marry Claudius after the king’s death.

The player king replies from many years of wisdom that things change, that love is unreliable. “Our wills and fates do contrary run.” The king, now tired, falls asleep. The player queen leaves.

On the side, Hamlet throws in clever comments to Gertrude and Claudius that smack of trying to get under the skin of the king and queen. Claudius wants to know what the play is called. Hamlet responds The Mousetrap. He adds that it is a play about a murder in Vienna and no big deal and that it would only bother the guilty.

The player of the king’s nephew enters. Hamlet tells Ophelia who it is Lucianus. Ophelia says that Hamlet is a good commenter. Hamlet, feeling frisky, continues with sarcasm and sexual inuendo.

Lucianus pours poison into the sleeping player king’s ears. Hamlet remarks that he poisoned him to get the kingdom and the king’s wife all to himself. Claudius stands up. He wants the play to stop. He wants to leave. Everyone except Hamlet and Horatio leave.

Hamlet mocks the departure with a few poetic lines and jokes that perhaps he could be an actor if everything else failed. Horatio agrees. And Horatio also agrees that that Claudius did react to the poison scene. Hamlet knows now that the ghost was telling the truth.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern show up and say that the king is angry and queen is upset. Hamlet’s replies in glib fashion. His two friends want to know what’s up with him. They tell Hamlet that the queen wants to see him.

When the players enter with recorders, Hamlet grabs one and asks if Guildenstern can play it. He says no. Hamlet then calls out his friends – he and Rosencrantz are trying to play him and can’t even play a simple recorder.

Polonius comes around and tells Hamlet that his mother wants to see him right away. Hamlet replies with bits of nonsense and Polonius goes along. Hamlet says he will go see her – soon. By himself he says, it’s the witching hour when really hellish things go on. He could behave like that with his mother but he puts thoughts in check: “I will speak daggers to her and use none.”

~~

A3S3: Claudius, speaking to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, says Hamlet is getting crazier by the hour. He doesn’t feel safe. So, he’s going to send them both with Hamlet to England on diplomatic business. They agree to go, with Rosencrantz saying that whatever happens to the king happens to everyone. They leave and Polonius enters.

He tells Claudius that Hamlet is on his way to his mother’s chamber and that he will hide in there and listen to her scolding Hamlet. He leaves.

Claudius, alone in his chamber, admits his crime:

O, my offence is rank, it smells to heaven;

It hath the primal eldest curse upon’t,—

A brother’s murder!

His Cain-like murder of his own brother comes with God’s curse. He’s finding it hard to pray. He’s not ruing what happened. He’s wondering if he can even repent of it, be pardoned of his sin and continue to live with all the gains (the kingdom and queen). He falls to his knees. What is not said is Claudius’ desire to murder again – this time Hamlet is in his sights.

Hamlet enters, intending to kill Claudius. He sees Claudius on his knees and thinks that if that guy dies while praying, he will receive grace, go to heaven, and be forgiven of his sins. Whereas his murdered father, King Hamlet, had no time to repent of his sins. He doesn’t consider it revenge by killing him now and sending him to heaven. Claudius must suffer the same purgatory

Hamlet, who knows that his mother is waiting for him, leaves the room. He says that he’ll wait to kill Claudius when Claudius acts up again in some ungodly way.

Claudius, getting up from his knees, considers his prayers useless.

My words fly up, my thoughts remain below.

Words without thoughts never to heaven go.

What is not said is Claudius’ desire to bring about murder again – this time of Hamlet in England. Hamlet missed his chance for revenge.

~~~

Prior to the Mousetrap play, Hamlet was a mess. Things in his world looked absurd and bleak. He had just returned home from studying in Wittenberg to a dark and vexing situation – something rotten in Denmark.

A ghost, looking like his dead father, appears from somewhere. Hamlet learns from the specter that it had been murdered by his uncle Claudius and that his mother quickly married him. The ghost orders Hamlet to avenge his death and go easy on his mother.

But should Hamlet, a theology and philosophy student, listen to the ghost from somewhere and do something irrevocable – kill Claudius – and end up in purgatory or hell? Is he required to deal with the unresolved past? These questions weigh on him.

In addition to the complex matter handed him, Hamlet, who was in line to be king when his father died, now wonders if those around him in Denmark can be trusted. And, a foreign prince seeking revenge is marching against the Danish kingdom. There’s a lot of vectors to think about.

It’s a situation so messed up that he thought about suicide.

Prior to the Mousetrap play, Hamlet was also very disappointed with himself for not being a man of action, of thinking too much. But with confirmation of Claudius’ guilt via the play, something has stirred in Hamlet. He’s ready, driven with revenge madness, to dispose of Claudius.

Claudius had taken action – murdered King Hamlet – without regard to a common understanding Rosencrantz had stated in obeying Claudius’ own protection order: whatever happens to the king happens to everyone. And now, Claudius is ready to dispose of the rightful heir to the throne to protect himself.

~~~

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark operates in a God-ordered moral universe with heaven, hell, sin, punishment. The undead figure, aware of this, goads Hamlet to commit murder to avenge his death and to also leave Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, to God’s judgement. The undead figure’s goading ultimately leads to many deaths including Hamlet’s.

The opening “Who’s there?” seems to also ask of the living – Hamlet – what kind of actor he is given the ultimate issues he faces. Pushed to the limits, will the center hold?

~~

A3S4: Getrude and Polonius are in the queen’s chamber waiting for Hamlet. Polonius wants Gertude to lay into Hamlet for the trouble he’s caused. When they hear Hamlet approach, Polonius hides behind a tapestry to listen in.

Hamlet, impatient, wants to know what his mother wants. She says that he’s insulted his (step-) father. Hamlet fires back saying that she’s insulted his father. Though he vented privately before, Hamlet is no holding back.

His mother, shocked, wonders if Hamlet has forgotten who she is. Hamlet’s response is pointed:

No, by the rood, not so.

You are the Queen, your husband’s brother’s wife,

And, would it were not so. You are my mother.

Hearing Hamlet’s denunciation, his mother now wants to bring others in. Hamlet tells her to sit down and not move. For, he wants to expose her true nature. She fears Hamlet will kill her with the sword in his hand. She cries for help. Polonius, from behind the curtain, also cries for help.

Hamlet smells a rat or rather, Claudius. He lunges and stabs the curtain with his weapon. His mother cries, “O me, what hast thou done?”

Hamlet replies, “Nay, I know not. Is it the King?

Gertrude: “Oh, what a rash and bloody deed is this!”

Hamlet:

A bloody deed. Almost as bad, good mother,

As kill a king and marry with his brother.

Gertrude: “As kill a king?”

Hamlet: Ay, lady, ’twas my word.

Hamlet pulls back the curtain and discovers Polonius, dead. He has nothing good to say about the busybody Polonius who, Hamlet deems, got his just deserts. Hamlet turns to his mother, for her just deserts – wring her heart with words of judgement.

She wants to know what’s she’s done to be treated so badly. Hamlet is ready to tell her – a deed so heinous that its judgement day on earth. She again wants to know what the deed is.

Hamlet then compares her former husband, his noble father to the scum that she hooked up with. He wonders how anyone, even impaired, could make such a decision. Reason has been a slave to desire, he says. She wants him to stop exposing her sin.

O Hamlet, speak no more.

Thou turn’st mine eyes into my very soul,

And there I see such black and grained spots

As will not leave their tinct.

But Hamlet continues.

O speak to me no more;

These words like daggers enter in mine ears;

No more, sweet Hamlet.

He rails against her going to bed with her villainous husband, a ragtag man who is but a small fraction of his father’s worth and who stole the crown.

The ghost enters. Hamlet sees the ghost. Gertrude does not. When Hamlet speaks to the ghost, Gertrude thinks he’s gone mad.

The ghost spurs Hamlet to back on the revenge track. He also cautions Hamlet not to overdo it with his mother, the weaker sex. The ghost leaves. Gertrude has not heard or seen anything of the ghost. She thinks Hamlet’s madness has him imaging all this.

But Hamlet protests, saying he is of sound mind. He then counsels her to not look at his madness but to look at her heart, to confess her sins, and repent. Her conscience is pricked by his words. Hamlet continues:

O throw away the worser part of it,

And live the purer with the other half.

Good night. But go not to mine uncle’s bed.

Assume a virtue, if you have it not.

Hamlet, who started out virtuous and is now heading to the dark side, wants his mother to be prudent and temperate. He wants her to at least pretend to be virtuous and by this, develop good habits. And that would mean her not having sex with Claudius and letting him deceive her in anyway about her son.

Hamlet then says good night to his mother and sorry about what happened to the dead guy, Polonius. He considers it God’s punishment for himself and Polonius. He

He reminds his mother that he’s off to England with two snakes in the grass, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. He’s expecting to see the plan Claudius has in place blow up in his face.

As he leaves, Hamlet drags Polonius body out of the room. He comments that the stiff was babbling politician who has finally shut up.

~~~

A4S1: Claudius enters and wants to know why Gertrude is so upset. She tells him about Hamlet’s “lawless fit” of madness that killed “a rat, a rat.” Polonius was dead. Claudius blames himself for not doing enough to stop the “mad young man.” He tells her that he’ll ship Hamlet off to England and work his magic to explain and excuse what happened.

Gertrude says that Hamlet had dragged the body off somewhere and that she sees a glimmer of good in the mad Hamlet – he weeps for what he has done.

Claudius summons Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and tells them to go look for Hamlet and recover the body. He tells Gertrude that he hopes they can come out of this scandal in good shape.

~~

A4S2: Rosencrantz and Guildenstern come across Hamlet and ask about the body. Hamlet gives no direct answer. He accuses Rosencrantz of being a “sponge” (spy) for Claudius and says “The body is with the king, but the king is not with the body. The king is the thing . . .” This last seems to be a riff on “the plays the thing.” Both lines, in Hamlet’s mind, refer to bringing the guilty party to justice.

Guildenstern doesn’t understand. So, Hamlet says the king is of no importance. (The crime is.) He wants to see the king and off they go.

~~

A4S3: Claudius, in the meantime, to his attendants:

I have sent to seek him and to find the body.

How dangerous is it that this man goes loose!

Claudius talks to them of being judicious on how Hamlet is handled. He is loved by the people so a fair-minded punishment must be seen by them and not the crime (which might expose more than Claudius wants known). His being sent away to England will look carefully considered. He ends by saying that a cancerous disease must be dealt with in extracting ways.

Rosencrantz enters and tells Claudius that Hamlet has not told him where the body is. Guildenstern brings Hamlet into the room. Claudius presses Hamlet for the location of the body. Hamlet responds with flippant riddles before revealing where the body is. The attendants go and look.

Claudius tells Hamlet that he will leave for England right away – for his own protection. Hamlet is happy about this. Before he leaves, Hamlet calls Claudius his mother – a jab based on Claudius being married – one flesh – with his mother.

Claudius sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to follow Hamlet to make sure he gets on the boat. Alone, he speaks of his hope that the king of England will obey the sealed orders sent with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The orders call for Hamlet to be put to death when he arrives.

~~

A4S4: Fortinbras, the Norwegian prince, arrives in Denmark at the head of his army. He sends his captain to the king of Denmark to ask for permission to cross the land on his way to attacking Poland. On his way the captain runs into Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who are on their way to the boat headed for England.

Hamlet asks the captain why Norwegian troops are in Denmark, who’s leading them and what are they after – the heart of Poland or just a outlying region. The captain explain that Fortinbras is leading the army to seize a small scrap of land that has no value to anyone.

Hamlet wonders if the Poles would defend such a target and the captain replies that they will. Before he thanks the captain for the information and says good bye to him, Hamlet stops to think about what he just heard.

He remarks that men are so driven that they will go to war at great cost of blood and treasure for pointless gain.

Rosencrantz wants Hamlet to get a move on. Hamlet says for them to go ahead and he’ll catch up. Hamlet wants some time alone to reflect on his own inaction.

Based on the resoluteness of a foreign prince risking life and limb by attacking something pointless, he realizes that thinking too much about whether to act is more cowardice than wisdom. He likens his inertia to that of being an animal that only eats and sleeps. Yet, he tells himself, he has more motive than Fortinbras – to mete out revenge for the murder of his father, King Hamlet. He determines right then and there:

O, from this time forth,

My thoughts be bloody or be nothing worth.

~~

A4S5: Gertrude enters the next scene telling a gentleman of the court that she doesn’t want bother with Ophelia’s loopy behavior. But Ophelia insists on being heard, the gentleman tells her. She’s saying all kinds of things related to the death of her father Polonius and conspiracy things that seem to implicate Gertrude. Horatio thinks she should speak to her. Gertrude, to herself, says that because of her nature everything looks like a disaster waiting to happen to expose her:

To my sick soul, as sin’s true nature is,

Each toy seems prologue to some great amiss.

So full of artless jealousy is guilt,

It spills itself in fearing to be spilt.

Ophelia enters and it is evident that the death of her father has affected her sanity (Just as the loss of Hamlet’s father affected his.). She sings nonsense songs and Gertude can’t get her to stop. Claudius enters and asks Ophelia how she is doing. She responds with nonsense that hints at her father’s death. When she leaves the room, Claudius says

O, this is the poison of deep grief; it springs

All from her father’s death. O Gertrude, Gertrude,

When sorrows come, they come not single spies,

But in battalions.

Claudius tells Gertrude that bad things are piling on. Polonius was killed, Hamlet has sent away for being dangerous, people are spreading rumors of the hasty funeral which looks like a cover up, and Ophelia has lost her mind. And now Laertes has returned from France and wants to the settle score. Claudius tells Gertrude that all this feels like be being murdered over and over again.

Laertes arrives with a raucous crowd shouting “Laertes will be king!” Doors are smashed open and they enter. Laertes wants to know where his father is. Gertrude clings to Laertes, holding him back from attacking Claudius. Laertes wants to know how his father was murdered. Claudius wants to prove to Laertes that he didn’t do it.

Ophelia enters and Laertes witnesses her madness. He vows revenge for the hellish suffering and torment brought upon his sister.

Claudius, to settle things in Laertes’ mind, says that he should bring his trusted friends and listen to the case he makes of his innocence. Laertes agrees and demands to know why his father was buried secretly and ignobly. Claudius says he has a right to know and

So you shall.

And where th’offence is let the great axe fall.

I pray you go with me.

~~

A4S6: Horatio, elsewhere in the castle, receives two sailors who have a letter from Hamlet. Horatio reads the letter out loud and learns that Hamlet’s ship to England was overtaken by pirates. Hamlet ended a prisoner on the pirate ship.

The pirates want a favor from the King of Denmark. The request is contained in letters the two sailors are holding. Hamlet asks Horatio to bring the sailors to king and then and come to him. He has a lot to tell Horatio about events and about Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The sailors will show Horatio the way to where he’s holed up.

~~

A4S7: While this happens, Claudius talks with Laertes. Claudius thinks Laertes should be satisfied with his explanation of his father’s death – by the same man who is trying to kil him. Laertes wants to know why the king didn’t act right away to bring the murderer to justice.

Claudius states that he held back because his mother and the people so love Hamlet. If he acted his wife and the people would turn against him.

Just then a messenger arrives with the sailor’s letters – one for Claudius and one for Gertrude. Claudius reads the letter out loud for Laertes to hear. Hamlet, it says, will return tomorrow and explain his return. Though not mentioned but what must have been on Claudius’s mind – his failed scheme to be rid of Hamlet via the king of England.

Laertes is happy about Hamlet’s return. Now he can face him man to man and avenge his father’s murder. Claudius agrees that Hamlet’s should be disposed of – he’s a threat to his kingdom. He tells Laertes to let him devise a way to do away with Hamlet that will appease even his mother. Laertes agrees to Claudius’s scheme only if it means Hamlet’s demise by his own hand.

Claudius gins up a scheme that involves a duel between Laertes and Hamlet. To set up this scenario, Claudius tells Laertes of a certain Frenchman’s high regard of Laertes’ fencing ability. He adds that Hamlet overheard the compliment and, out of jealousy, wanted to fence Laertes to see who was the better dueler. Is the devious Claudius lying?

After Claudius confirms that Laertes is with him in plan, that Laertes won’t lose the impulse to kill Hamlet, he tells Laertes that he’ll get the people to promote the competition, that there will be bets placed and that Laertes can chose a sharpened sword beforehand to do the deed.

Laertes says he’s gotten ahold of poison oil to put on the tip of his sword. And Claudius speaks of a backup plan: get Hamlet thirsty and he’ll give him a poison drink.

Gertrude enters with terrible news: Laertes’ sister Ophelia has drowned. Gertrude softens the blow for Laertes by implying it was an accident and using imagery of her female connection with nature. (She did not treat her grieving son Hamlet with compassion.)

How did she know the details? Perhaps she witnessed it from a castle window or? Anyway, Laertes is crushed – both father and sister are dead. Claudius, worried that the upset Laertes is beyond his control, follows him with Gertrude.

~~~

A5S1:

Is she to be buried in Christian burial, when she wilfully seeks her own salvation?

So says one gravedigger to another in the graveyard of the church. They are excavating a burial plot for Ophelia and exchange thoughts about whether she should receive a Christian burial. It seems to them that she committed suicide, though the coroner called it self-defense. One gravedigger remarked that it is more like self-offense and goes on to say that the wealthy, who end their lives in unchristian ways, get their way in the end.

As they work, the first gravedigger poses a riddle to the second gravedigger: “What is he that builds stronger than either the mason, the shipwright, or the carpenter?” The second gravedigger answers that it must be the gallows-maker, “for his frame outlasts a thousand tenants.”

The first gravedigger agrees that the gallows have a purpose, but then says

Cudgel thy brains no more about it, for your dull ass will not mend his pace with beating; and when you are asked this question next, say ‘a grave-maker’. The houses he makes last till doomsday. Go, get thee to Yaughan; fetch me a stoup of liquor.

The second gravedigger goes off and the first shovels and sings.

Hamlet and Horatio arrive at the graveyard at a distance from Ophelia’s plot. We don’t know why Hamlet decided to go to the graveyard. Perhaps, to contemplate his own life and death. He’s been away and does not know that Ophelia is dead.

They hear the gravedigger singing while digging a grave. Hamlet notices the dissonance and a skull that the gravedigger throws up from the pit.

Does what follows relate to the opening Who’s there? Hamlet suggests to Horatio whose skull it might be – Cain’s, a courtier, or Lord So-and-So – and says it’s now the property of Lady Worm and quite a reversal of fortune.

The gravedigger, still digging and singing, throws up another skull out of the pit. As before, Hamlet proposes to Horatio whose skull it belongs to – a lawyer or a landowner. For both, their abilities and property are no longer of use to them. They no longer have a share in what is done under the sun.

Hamlet turns from contemplating death and human remains to the gravedigger. He wants to know whose grave he is digging. This begins the jaunty gravedigger’s wordplay in answer to each of Hamlet’s direct questions. Finally, the gravedigger says

One that was a woman, sir; but, rest her soul, she’s dead.

Hamlet asks: How long hast thou been a grave-maker? The gravedigger, not knowing who he is talking to, answers that it has been so since Hamlet’s father defeated Fortinbras. Hamlet: How long ago was that? He answers the day that Hamlet, the one who went crazy and was sent to England, was born. He goes on to say that he was sent to England because no one will care: There the men are as mad as he.

The conversation briefly turns to how long a body will live in a grave before it rots. Then the gravedigger pulls up a skull that has been buried for twenty-three years. Turns out that it is the skull of Yorick, the king’s jester. He hands it to Hamlet.

Hamlet reminisces for moment about the goods time he had with Yorick when he was a young boy. Then he turns to Horatio and wonders if Alexander the Great and the emperor Caesar looked like this after they were buried. These great men, he muses on another reversal of fortune, became dust and could be used as mud to plug up holes.

A funeral procession enters the churchyard following a coffin: Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes, and mourning courtiers. Hamlet wonders who’s in the coffin. He remarks that it’s not much of a procession; someone in a rich family must have taken their own life. He watches the proceedings.

Laertes asks the priest what other rites he can give the girl and the priest answers that he has done as much he could for someone with a suspicious death. Laertes is incensed and lays into the priest about his sister. Hamlet finds out that Ophelia is being buried.

Gertrude throws flowers onto the coffin while ruing that the flowers were not for Hamlet’s wedding to Ophelia.

Laertes curses the man who made her go mad. He jumps into the grave to hold Ophelia once more.

Just moments ago, Hamlet was fondly remembering Yorick. Now he is confronted by the death of Ophelia. He is overwhelmed:

What is he whose grief

Bears such an emphasis? whose phrase of sorrow

Conjures the wand’ring stars, and makes them stand

Like wonder-wounded hearers? This is I,

Hamlet the Dane.

Not to be outdone by Laertes’ grief, Hamlet also jumps into the grave. Laertes tells him to go to hell. The two begin to grapple. Hamlet says that even though he is not quick to anger, he has something dangerous inside him that Laertes should take into account. What could that be?

Claudius and Gertrude have the attendants pull them apart.

Then Hamlet, in his agony, expresses his great love for Ophelia – a love greater than her brother’s affections. He quantifies his ardor in absurd ways. And the King and Queen think he’s insane.

When Hamlet storms off, Claudius tells Gertrude to have the guards keep an eye on him. He tells Laertes to be cool. Hamlet, the problem, will be dealt with soon.

~~

A5S2: Hamlet and Horatio are now alone. Hamlet has walked off his momentary madness and wants to discuss with Horatio his recent journey. He casts the decisions he’s made in terms of a struggle that kept him from sleep.

He then praises impulsiveness as the means to getting things done when one is slow to act. This, he says, shows that God is a work even when our plans are messed up:

Rashly,

And prais’d be rashness for it,—let us know,

Our indiscretion sometime serves us well,

When our deep plots do pall; and that should teach us

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will.

This harkens back to Hamlet’s agency in his line The time is out of joint. O cursèd spite That ever I was born to set it right! But is Hamlet trying to force God’s hand with rash actions?

Hamlet goes on to tell Horatio, that while on the ship to England, he found Claudius’ letter to the King of England. It was to be delivered by Hamlet’s close friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The letter contained the usual political courtesies AND a request to cut off Hamlet’s head with a dull axe! Hamlet shows Horatio the document, as he can’t believe it.

Hamlet then reveals that he penned a new letter in the proper script and sealed it with his father’s signet ring still in his possession. The new letter addressed the king of England as if in Claudius’s own words. It requested that the two men who delivered the letter would be put to death at once without time to confess to a priest.

Horatio says that those two are really in for it. Hamlet says he’s not sorry at all for they involved themselves in matters between two worthy opponents. Then he proclaims his moral right to do away with Claudius. He lays out the charges against him:

Does it not, thinks’t thee, stand me now upon,—

He that hath kill’d my king, and whor’d my mother,

Popp’d in between th’election and my hopes,

Thrown out his angle for my proper life,

And with such cozenage—is’t not perfect conscience

To quit him with this arm? And is’t not to be damn’d

To let this canker of our nature come

In further evil?

Horatio remarks that Claudius will soon find out what happened to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Hamlet agrees the time is short but says that in the meantime he has time to work his plan. He then regrets losing control with Laertes – they both grieve the loss of Ophelia, they both want to avenge the death of a loved one. He says he will treat him well from now on.

Hamlet apologizes to Horatio for his over-the-top behavior but not to Laertes. He also blames Laertes for his actions – it was Laertes’ overwhelming show of grief that set him off. And Hamlet never confesses or repents of his cruel behavior with Ophelia, behavior that played a role in her despair and suicide. Has Hamlet stopped listening to his conscience?

With hat in hand, Osric, a young courtier, arrives. He has a message from the king for Hamlet. Hamlet makes snide comments about him to Horatio and toys with Osric about his hat and the weather. You get the idea that Hamlet will not suffer fools. Osric is a toady who agrees with Hamlet about everything including opposites that Hamlet harries him with. The conversation is a duel between a wit and a twit.

Osric goes on blustering about how wonderful Laertes is. Hamlet, not sure where Osric is going with all this, adds his own praise about Laertes and asks why he is being talked about. Horatio also hopes to get the reason Osric is there.

When Osric finally gets to the point, he says that Laertes is unrivaled at fencing and that the king has placed a large bet on a fencing contest between Hamlet and Laertes. Laertes, the better fencer, is given a handicap of three hits to win. He wants to know if Hamlet agrees to the duel. Hamlet says OK.

After Osric leaves to notify the king, Hamlet and Horatio comment on Osric one more time saying, in effect, that he’s a frivolous person and full of hot air.

A lord arrives. He asks if Hamlet is ready to duel or wait till later. Hamlet says he’s ready to duel. The lord says that the queen wants Hamlet to speak to Laertes before the duel in a civil manner. The lord leaves.

Horatio advises Hamlet against dueling – he will lose. Hamlet brushes this off saying that he has been practicing fencing while Laertes has been in France. He thinks he will win and yet something inside tells him it will go the other way. Horatio tells him to trust that feeling. Hamlet brushes off the advice as superstitious and then launches into a “Let be” to-be-or-not-to-be fatalistic take of the situation.

Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes, Osric, attendants, and lords enter with fanfare. Fencing foils and flasks of wine are brought in with them. Claudius has Hamlet shake Laertes’ hand as a civil gesture.

Hamlet offers an apology to Laertes for his unseemly behavior. But the apology is an insanity defense. Hamlet claims that he was not in his right mind, as everyone knew, and that he was not responsible for any premeditated action against Laertes.

Laertes accepts Hamlet’s show of love but can’t accept forgive him. For him, the death of father and sister warrant further insight as to how honor would avenge them. Laertes, of course, already knows what will happen in the next minutes.

Hamlet and Laertes pick their foils and get ready to fence.

Claudius, the schemer, shows bogus support for Hamlet as he wants Hamlet to not hold back – until his death. If Hamlet strikes first, Claudius will order military salutes. He’ll drink to Hamlet’s health and then drop a very expensive pearl into the glass for Hamlet to drink. What he drops in the glass, of course, is poison. Trumpets sound and the duel begins.

Hamlet and Laertes engage their blades. Hamlet makes the first hit. Drums and trumpets sound, and so does a cannon. Claudius drops a pearl into a goblet and says it’s for Hamlet. He wants him to drink it. Hamlet wants to finish the round first. They continue fencing.

Claudius and Gertrude exchange words about her son Hamlet. Then Gertrude picks up the pearl/poison-laced goblet and drinks to Hamlet’s health. Claudius tells her not to drink it and she does anyway, in an act of defiance toward Claudius. Claudius knows it’s only a matter of time for Gertrude’s demise.

Hamlet defers again from drinking the wine. Gertrude wants to wipe his brow. Hamlet wants Laertes to fence like he means it. They go back at it. This time, Laertes wounds Hamlet and in the scuffle that follows they end up with each other’s sword. Hamlet wounds Laertes.

Gertrude, the poison haven taken hold, falls to the floor. Both fencers are wounded and bleeding. Osric asks Laertes how he feels and he responds that he is like one caught in his own trap: I am justly killed with mine own treachery.

Hamlet asks about his mother. Claudius says she fainted at the sight of blood. Gerturde speaks one last time:

No, no, the drink, the drink! O my dear Hamlet!

The drink, the drink! I am poison’d.

Gertrude dies. Hamlet reacts:

O villany! Ho! Let the door be lock’d:

Treachery! Seek it out.

Laertes, dying, tells Hamlet that his sword had a poison tip and that his plan to kill him backfired. He can blame the king for poisoning his mother.

Hamlet takes the poison-tipped sword and wounds Claudius. The court yells “Treason!” Then Hamlet forces Claudius to drink from the poison-laced goblet, saying

Here, thou incestuous, murderous, damned Dane,

Drink off this potion. Is thy union here?

Follow my mother.

Claudius drinks and dies. Hamlet achieves his father’s vengeance after seeing his mother poisoned by Claudius’ scheme to do him in.

With his last breath, Laertes tells Hamlet that Claudius deserved what he got – the poisoner poisoned himself. Then, laying all the blame on Claudius, he wants to clear the slate with Hamlet before he dies:

He is justly serv’d.

It is a poison temper’d by himself.

Exchange forgiveness with me, noble Hamlet.

Mine and my father’s death come not upon thee,

Nor thine on me.

Hamlet, dying, replies that heaven will not hold Laertes responsible for his death. He then bids adieu to the Wretched queen and tells those who were watching in horror that, if he had time, he could explain things. He tells Horatio to report what happened. Horatio balks at the suggestion and wants to end his life like an ancient Roman with the remainder of the poisoned drink. Is everyone, as said of Ophelia, seeking their own salvation?

Hamlet says no and takes the cup away from Horatio. Horatio must live to tell Hamlet’s story.

As th’art a man,

Give me the cup. Let go; by Heaven, I’ll have’t.

O good Horatio, what a wounded name,

Things standing thus unknown, shall live behind me.

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart,

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story.

As he is saying this, Hamlet hears the sound of a military march. He asks about it. Osric says that young Fortinbras, returning from his conquest in Poland, is approaching. Hamlet says that prince Fortinbras will likely be chosen for the Danish throne. Hamlet gives his approval and tells Horatio to explain to him what happened. The unresolved recent past can’t stay that way. The rest is silence as Hamlet dies.

Horatio:

Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince,

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.

Why does the drum come hither?

Fortinbras and the English Ambassador enter. They look around at the gruesome scene wondering what happened. The English Ambassador says that his king carried out the Danish king’s order – Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead. He wants to know who will thank the king.

Horatio, pointing to Claudius’ corpse, replies that it won’t be this guy. He never ordered their death. He then requests that these bodies be displayed and that he is given the opportunity to tell

How these things came about. So shall you hear

Of carnal, bloody and unnatural acts,

Of accidental judgements, casual slaughters,

Of deaths put on by cunning and forc’d cause,

And, in this upshot, purposes mistook

Fall’n on the inventors’ heads. All this can I

Truly deliver.

Fortinbras is eager for himself and other noble people to hear what Horatio has to say. He speaks of his opportunity and right to claim the Danish throne. Horatio tells him that Hamlet talked about this. He will tell Fortinbras more later. But first things first.

Fortinbras orders four captains to carry Hamlet and place him on a stage and to give him military honors. He would have been a great king, he says.

Looking at the bodies strewn in the court, he says it’s something one would see on a battlefield but here, something went terribly wrong. (More rottenness in Denmark?)

Fortinbras orders guns and cannons to be fired to honor Hamlet as a great soldier. (Was he a great soldier in the battle of life?)

Afterthoughts

Hamlet starts out as a virtuous young man operating with a deep sense of morality within a Christian cosmology. But grief, the revenge demand placed on him by a supernatural being, betrayal, and existential despair changes him. Listening to a dis-embodied spirit, he ends up a dis-embodied spirit.

What if Hamlet didn’t listen to the ghost? And, what if Hamlet didn’t listen to his pride and end up in a fencing duel with the son of the man he murdered hosted by the man who murdered his father? Did he see it as a way to choose his own salvation?

With the Mousetrap play, Hamlet verified what the ghost said – that Claudius poisoned his father. But Hamlet didn’t act when he heard Claudius confessing his guilt in his chamber. He thought there would be a more opportune, as in no chance for Claudius go to heaven, moment. He dithered and many lives thereafter received a violent death, a death without confession of sins. Death count since: Polonius, Ophelia, Rosencrantz, Guildenstern,Laertes, Gertrude, Claudius, and Hamlet.

~~~

Will the two gravediggers reprise their humorous banter while digging the grave of the newly dead? Will they speak of the deceased as they spoke of Ophelia:

Is she to be buried in Christian burial,

when she willfully seeks her own salvation?

Will they ponder the reversal of fortunes as did Hamlet?

~~~

As it was common for royal marriages to create alliances, was Queen Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, a foreigner? Was she perhaps German and the link to Wittenberg?

~~~

There are more ghosts at the end than at the beginning.

~~~~~

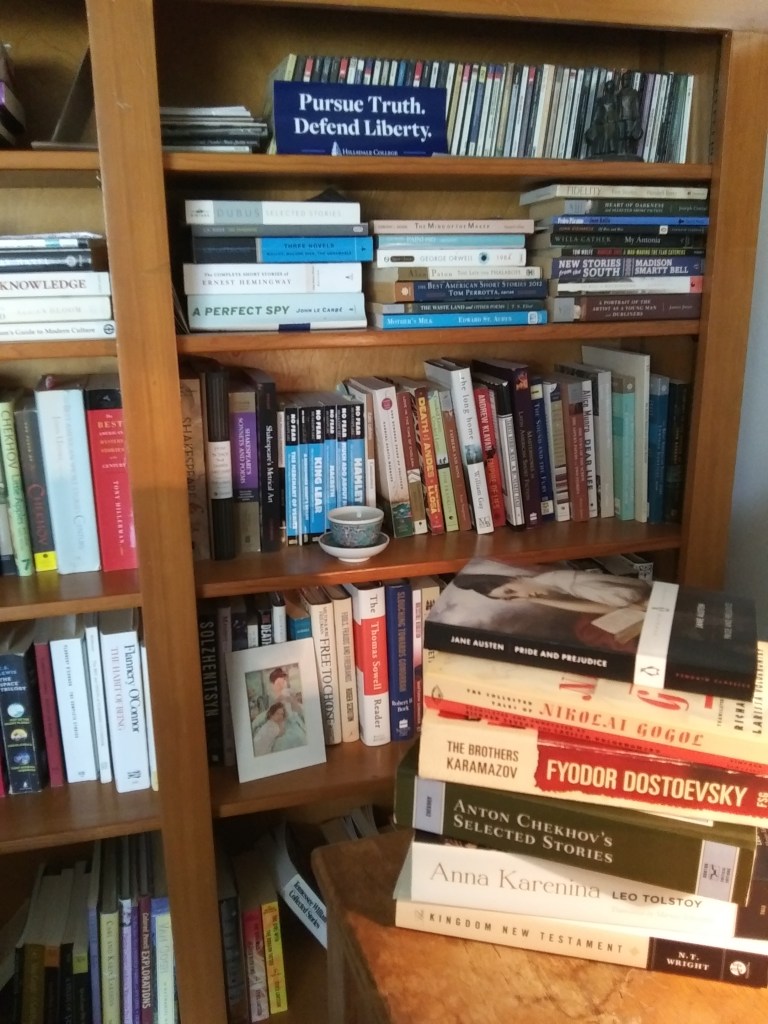

The Play’s the Thing

You’ll find excellent discussions on all five acts of Hamlet and a Q&A session podcast at the link below.

Tim McIntosh: https://www.timteachesshakespeare.com/about

Heidi White: https://circeinstitute.org/blog/jet-popup/read-more-about-heidis-class/

Andrew Kern: https://circeinstitute.org/staff-and-board/

It’s finally time to discuss the grandaddy of all of Shakespeare’s plays! That’s right, it’s time for Hamlet and Tim, Heidi, and special guest Andrew Kern are ready to dig deep. In this episode they discuss why this play matters so much, the initial structure of the play, the themes and problems Act I introduces, and much more.

Hamlet: Act I (rerun) – The Play’s the Thing | Acast

Note: To begin reading Hamlet in plain English, start with Hamlet: No Fear Shakespeare.

~~~~~

Interesting Background:

For your intent

In going back to school in Wittenberg,

It is most retrograde to our desire:

And we beseech you bend you to remain

Here in the cheer and comfort of our eye,

Our chiefest courtier, cousin, and our son.

-Claudius to Hamlet, A1S2 (emphasis mine.)

A paper read today at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Toronto, Canada, offers a new interpretation of Shakespeare’s play Hamlet.

The paper, by Peter D. Usher, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State, presents evidence that Hamlet is “an allegory for the competition between the cosmological models of Thomas Digges of England and Tycho Brahe of Denmark.”

ABSTRACT

A New Reading of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

I argue that Hamlet is an allegory for the competition between the cosmological models of Thomas Digges (1546-1595) of England and Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) of Denmark. Through his acquaintance with Digges, Shakespeare would have known of the essence of the revolutionary model of Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) of Poland, and of Digges’ extension of it. Shakespeare knew of Brahe, and named Rosencrantz and Guildenstern for his forebears. I suggest that Claudius is named for Claudius Ptolemy (fl. 140 A.D.) who perfected the geocentric model. It has been suggested that Polonius is named for a Brunian character Pollinio, an Aristotelian pedant and a suitable attendant to Claudius. Hamlet is a student at Wittenberg, a center for Copernican learning, which Brahe attended too. I suggest that the slaying of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern is the Bard’s way of killing the Tychonic model, while the death of Claudius signals the end of geocentricism. But the climax of the play is not the death of any of the chief protagonists; it is Fortinbras’ triumphal return from Poland and his salute to the ambassadors from England. Here Shakespeare praises the merits of the Copernican model and its Diggesian extension. Thereby he defines poetically the new universal order and humankind’s position in it. In the talk I present both historical and literary evidence in support of the present interpretation. If it is essentially correct, this reading suggests that Hamlet evinces a scientific cosmology no less magnificent than its literary and philosophical counterparts. While the last year of the sixteenth century saw the martyrdom of Bruno, the first year of the seventeenth century sees the Bard’s magnificent poetic affirmation of the infinite universe of stars.

Peter D. Usher, Penn State

https://science.psu.edu/news/astrophysicist-finds-new-scientific-meaning-hamlet

~~~~~