The Unbroken Chain of Truth in the Lives of Broken People

March 30, 2024 Leave a comment

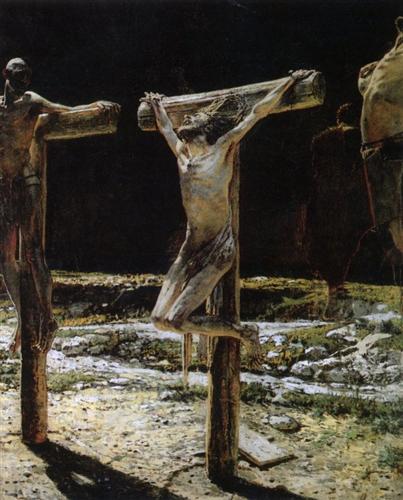

Our common understanding of what Peter’s betrayal of Jesus meant. Our shared history of misery and redemption. Our interrelated human experience of being guided by truth and beauty. Each of these connections are considered by a twenty-two-year-old clerical student named Ivan Velikopolsky in the very short story The Student (1894) by Anton Chekhov.

Things start out fine for hunter Ivan on Good Friday. The weather is agreeable. But when it begins to grow dark the weather turns cold and stiff winds blow. He starts to walk home.

On the path, he feels that nature itself is “ill at ease” by the change in weather and that darkness in response is falling more quickly. He senses overwhelming isolation and unusual despair surrounding him and the village three miles away where he spots the only light – a blazing fire in the widow’s garden near the river.

As he walks, he remembers what is waiting for him at home – a miserable situation that he sees as the desperation, poverty, hunger, and oppression of what people have dealt with over time and that it’s always been this way no matter the secular changes by those who come along. He doesn’t want to go home. Instead, he walks over to the campfire at the widow’s garden.

There, by the fire, are two widows – Vasilisa and her daughter Lukerya. He greets them and they talk.

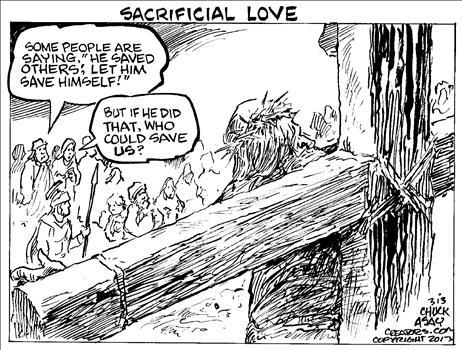

Ivan relates the gospel events to the two widows. This has an acute effect on them. As he heads home, Ivan reflects on the implications of this and has an epiphany.

“At just such a fire the Apostle Peter warmed himself,” said the student, stretching out his hands to the fire, “so it must have been cold then, too. Ah, what a terrible night it must have been, granny! An utterly dismal long night!”

. . .it was evident that what he had just been telling them about, which had happened nineteen centuries ago, had a relation to the present — to both women, to the desolate village, to himself, to all people.

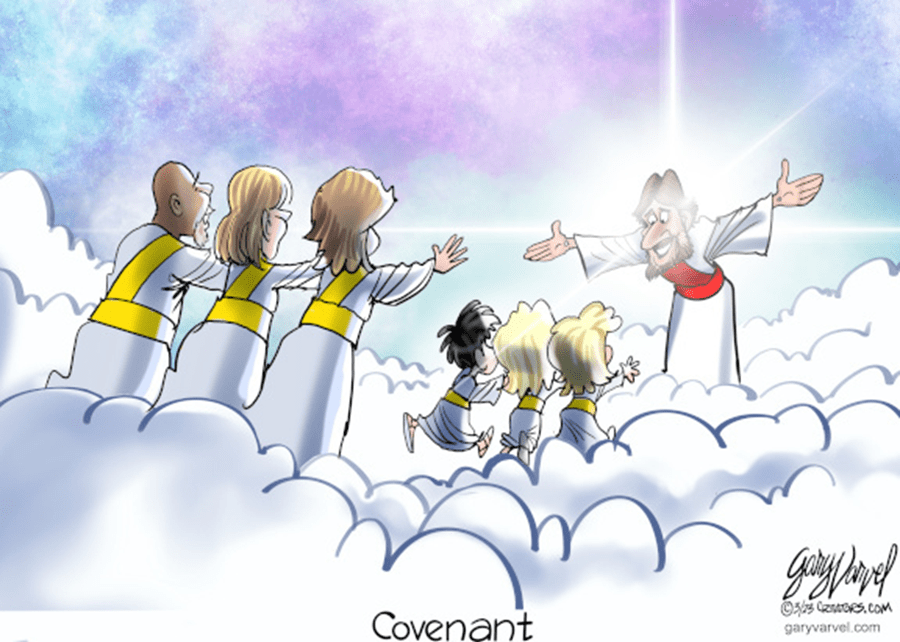

He returns home with a different outlook. He sees the “same desperate poverty and hunger, the same thatched roofs with holes in them, ignorance, misery, the same desolation around, the same darkness, the same feeling of oppression” differently – with an attitude of “unknown mysterious happiness”. There’s a sense of resurrection in Ivan’s attitude as he rises out of the despondency of dark winter’s return to a new life of hope based on the human connection to enduring truth and with Easter on the horizon.

Was Ivan’s new attitude born out of the women’s reaction that signaled an age-old inherent understanding of what the betrayal of truth produces?

It seems to me that Ivan is more than just a clerical student. He’s also a student of history and cultural anthropology. And he knows scripture. He is able to see our common plight and our common redemption through the broken lives of others.

I’m not going to share any more of this gem of a very short story (2 min. read). Ivan has more to say to us from his epiphany. I recommend reading the story before listening to the audio version of it with commentary at the end.

The Student was written 130 years ago. Chekhov’s realist fiction hands to readers today one end of an unbroken chain of truth.

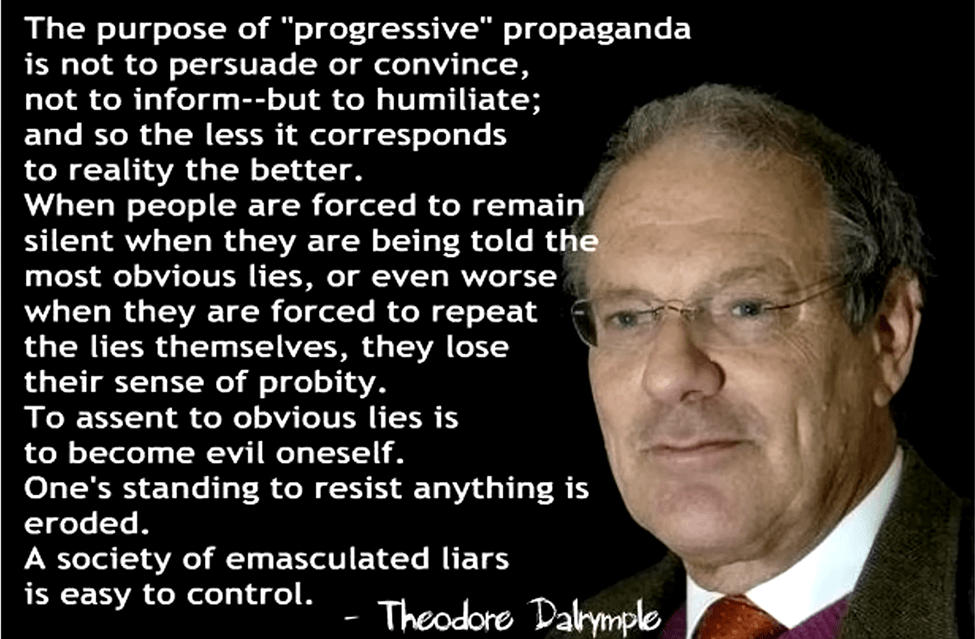

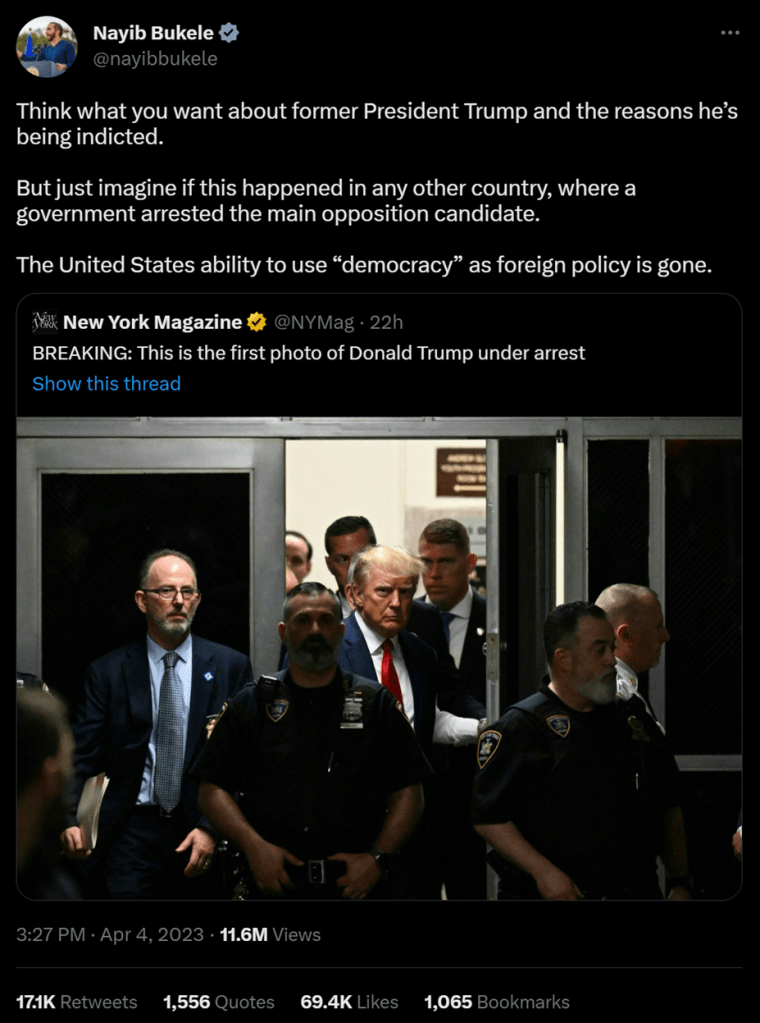

Will the human condition improve with Progressivism or when humans stop betraying the truth and seek what is above instead of materialism?

John Donne wrote “No man is an island entire of itself”. Certainly, no man is a context entirely of himself.

And Thomas Dubay said

The acute experience of great beauty readily evokes a nameless yearning for something more than earth can offer. Elegant splendor reawakens our spirit’s aching need for the infinite, a hunger for more than matter can provide.

~~~~~

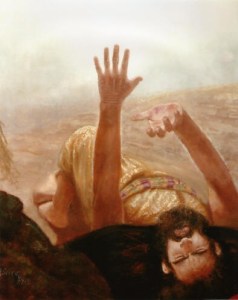

Beauty out of brokenness?

“Poetically translated to “golden joinery,” kintsugi, or Kintsukuroi, is the centuries-old Japanese art of fixing broken pottery. Rather than rejoin ceramic pieces with a camouflaged adhesive, the kintsugi technique employs a special tree sap lacquer dusted with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. Once completed, beautiful seams of gold glint in the conspicuous cracks of ceramic wares, giving a one-of-a-kind appearance to each “repaired” piece.”Kintsugi, a Centuries-Old Japanese Method of Repairing Pottery with Gold (mymodernmet.com)

“The aesthetic that embraces insufficiency in terms of physical attributes, that is the aesthetic that characterizes mended ceramics, exerts an appeal to the emotions that is more powerful than formal visual qualities, at least in the tearoom. Whether or not the story of how an object came to be mended is known, the affection in which it was held is evident in its rebirth as a mended object. What are some of the emotional resonances these objects project?

“Mended ceramics foremost convey a sense of the passage of time. The vicissitudes of existence over time, to which all humans are susceptible, could not be clearer than in the breaks, the knocks, and the shattering to which ceramic ware too is subject. This poignancy or aesthetic of existence has been known in Japan as mono no aware, a compassionate sensitivity, an empathetic compassion for, or perhaps identification with, beings outside oneself. It may be perceived in the slow inexorable work of time (sabi) or in a moment of sharp demarcation between pristine or whole and shattered. In the latter case, the notion of rupture returns but with regard to immaterial qualities, the passage of time with relation to states of being. A mirage of “before” suffuses the beauty of mended objects.”

Christy Bartlett, Flickwerk: The Aesthetics of Mended Japanese Ceramics (12/51

“What kind of a church would we become if we simply allowed broken people to gather, and did not try to “fix” them but simply to love and behold them, contemplating the shapes that broken pieces can inspire?”

― Makoto Fujimura, Art and Faith: A Theology of Making

Mending Trauma | Theology of Making (youtube.com)

~~~~~