These Things Happen

January 7, 2026 Leave a comment

The Victorian style houses on Rosy Hill Street, adorned earlier in the year with roses, hydrangeas, and ornamental grasses, were now festooned with glowing Christmas light bulbs. Passers-by would also behold Santas, reindeer, snowmen, candy canes, nutcrackers, candles, and festive garlands and wreaths. Looking inside, they could catch a glimpse of the stir of Christmas morning. Except at the Arts and Crafts Victorian house near the top of Rosy Hill Street. The Healey family – Tom, Cheri and their two young children, Alan and Angeline – was five hundred miles away at the bedside of Donna, Tom’s sister.

Two days before Christmas Tom received a call from Haven Hospice Care in Brent telling him that his sister was near death. This was a shock to Tom. He didn’t know that his sister had been ill. He knew her to be an independent sort. She lived alone and said little about herself when asked.

The day before Christmas, the Healey family arrived at the hospice. Tom’s sister was unresponsive to his voice and the presence of anyone in the room. Tom asked the attending nurse about his sister and was told that her condition had been decreasing rapidly. The doctor had ordered tests. He would be there in the morning and would have the details.

That night, at the motel, Tom called Roger to ask about Foster. Before making the trip, Tom asked his neighbor Roger Graybill if he would take their dog Foster out for walk and feed him while they were away. Roger agreed. Tom said he didn’t know how long he would be gone. He would call.

“Hi neighbor. How did it go today with Foster?” Roger said he and Foster went for a couple of walks and Foster was fed. Roger asked about Donna.

“It looks like she has rapidly progressive dementia. They’re telling me she doesn’t have much time left. I’ll talk to the doctor tomorrow.”

Christmas morning Tom drove over to Haven Hospice. Cheri stayed at the motel with the kids. They wanted to go swimming and have hot chocolate in their room and some vending machine candy.

Tom met with the doctor who told him how it happened that Donna was brought to the hospice.

“A neighbor had seen Donna walking down the sidewalk in her nightgown and cursing. The neighbor walked Donna back to her house, found her robe and purse, and then brought her to the hospital. Donna’s ID bracelet had your phone number. That’s how we knew to call you.”

“When I met her, her muscles were twitching and she was having trouble with coordination. Her health and her nervous system were swiftly deteriorating. We had no medical history on her but we did run seDonnal tests. EEG, MRI, a spinal tap to check the level of proteins in the spinal fluid, and a new test that detects abnormal proteins, known as prions, that damage the brain, that cause CJD.”

“CJD?” Tom asked.

“Donna has a rare neurodegenerative disorder called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or CJD. That’s why we brought her to hospice care.” The doctor then asked Tom if he had noticed any memory loss, confusion, personality shifts and coordination issues with Donna.

“I live five-hundred miles away. She never mentioned anything in her occasional emails. I didn’t receive a reply to my last email.”

“It is likely,” the doctor replied, “that she wasn’t able to respond.”

Tom was stunned by the report. Donna lay before him as if asleep. She occasionally moaned and when she opened her eyes for a few moments she stared at the ceiling and didn’t notice Tom in the room.

He stayed seDonnal hours at his sister’s bedside holding her hand and hoping for a response. He later returned to motel and told Cheri all that he had learned as they sat on the edge of bed together.

“The hospice will call if anything changes.”

“What do we do?” Cheri asked. “Do we wait there?”

“We wait for now. Tomorrow, I’ll go over to her house and see what’s what.”

~~~

The next day Tom went over to Donna’s house. A neighbor woman came out and called to Tom when she saw him at the door. After Tom explained who he was, she explained that she was the one who found Allsion walking down the street.

“I walked Donna back home, grabbed her purse and the house keys and a robe, locked the door and took her to the hospital.” She handed Tom the house keys.

“These things happen you know,” Janice began. “My father has the same thing going on. He’s at a memory care center with dementia.”

Tom said that he had no idea that his sister was living like this. “She never said anything and I live so far away from her. How could I know?”

“I checked on her a couple of times,” Janice said. “I could see mail piling up. I’d knock and she’d come to the door and I’d ask how she was and if she needed help and she’d look at me as if I was from another planet like my father does. She never said anything when I handed her the mail and that was that until a couple of days ago.”

Tom thanked Janice for helping Donna. He gave her a hug and she returned home.

Before going in, Tom grabbed all of the mail in the box and on the step. Many were past due notices.

Inside, he found disorder and a need to clean but nothing terrible. Books were the only that thing Donna hoarded.

He threw out old food, cleaned, did laundry and put the house in order. He went to work sorting out all of the financials his sister hadn’t been able to handle. He called the mortgage company and all her creditors, told them situation, and said that he will settle what she owes. He asked each for more time. That night he returned to the motel to be with his family.

After spending three nights at the motel – staying there so the kids could go swimming as a Christmas gift – Tom moved the family to Donna’s house. From there he would go see Donna during the day.

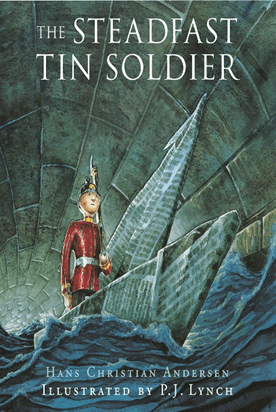

The first night in the new place, Alan and Angeline were tucked into their new sleeping bags. Tom read from Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales. He found the book on the over stacked bookshelf.

After reading The Steadfast Tin Soldier, Tom thought the kids were asleep. But four-year-old Alan sat up in his sleeping bag, rubbed his eyes, looked all around and asked his father if they were in a story like the Tin Soldier. His father thought for a moment and said “We are in a story, alright. In a story where curious things can happen. We must be like the Steadfast Tin Soldier no matter what.”

Tom continued to sit with Donna each day. He would take her hand and squeeze it. She would gasp and then return to her dormant state. The nurse continued to monitor her vitals. There was no sign of what was next, of what to do.

Tom called Roger. Roger said that all was well with Foster. “He’ll stay with us until you return.” And, “to not worry about things here. I’ll collect the mail and give it to you when you return.” Tom thanked Roger. He had forgotten about the mail. And he told him that Donna’s condition hadn’t changed.

~~~

New Years Eve, Roger and his wife went out for brunch with some friends. Jack, their sixteen-year-old son, was asked to feed and walk Foster while they were gone.

After his parents left, Jack finagled the lock on the liquor cabinet and was able to get in. He poured some Vodka into a plastic cup, grabbed a pack of cigarettes from the carton and a lighter, and closed the cabinet. He wanted to sneak a smoke before walking the dog. So, he grabbed the key to Healy’s garage.

Outside, the wind was stiff and icy cold. He turned up his jacket collar and walked over to the one car garage holding the cup of Vodka. He unlocked the door and stood inside, out of the wind, to smoke a cigarette. He didn’t want anyone, especially his parents, to see him.

He downed the Vodka and it burned his throat. He tossed the cup into a can by the garage door, lit the cigarette, and grumbled to himself about having to deal with the little beast. After one last long drag on the cigarette, he flicked the butt into the can, locked the garage door, and headed back to his house. He leashed Foster and went out for a long walk down the block looking at Christmas lights.

Twenty minutes into his walk, Jack came up to a man with his dog. Jack said hello and the man pointed behind Jack and said “Look! There’s a smoke over there. I don’t think it’s fireplace smoke. It is black.” Jack turned around and saw smoke billowing above the Healy garage. He hurried back up the street and froze when he saw flames shooting up around the garage door.

He didn’t know what to do and he knew what he had to do. He didn’t want anyone to find out that he was the one that caused the fire and he didn’t want the Healy’s garage and house to burn down. He knew about the wooden trellis connecting the detached garage with the house. He passed through it earlier.

Neighbors were gathering on the sidewalk and cars began to stop. A man was knocking on the Healy front door. Someone must have called 911. He heard sirens off in the distance. He wouldn’t dare go near the house now.

He wondered what the neighbors were thinking when they saw him with Foster. Would it look like he wasn’t around when the fire started. He wondered what his father would think. Would he believe that the fire could have started on its own? Don’t things just happen to catch fire because of some spark? These things happen, don’t they? Standing in his driveway, he rehearsed his cover story.

The fire was now engulfing half of the old garage and half of the trellis. And he had a terrible thought. What if the fire came was blown over to his house. Fire trucks pulled up.

He ran behind his house, took the cigarettes and lighter out of his pocket, and buried them in the trash can by the back door.

~~~

Roger and his wife came home and saw fire trucks in front of their neighbor’s house. Roger parked down the street and he and his wife rushed up as close as they could to see. They saw that the garage, Tom’s reupholster and furniture repair workshop, was burning to the ground. Firemen were shooting water across what was left of it and spraying the side of the house. The wind had swept the fire across to the house.

The painted facade of sage green and reddish-brown, the decorative gables, the wide, welcoming front porch on the east side of the house was being eaten away by the fire. In the front yard, the small nativity scene that Tom set out before Christmas – the manger, the straw, baby Jesus, Mary, Joseph, the shepherds and angels – had been knocked over. Hosed down, the figures began to ice over.

People were wondering if anyone was at home. Roger told a fireman that the family was out of town dealing with something else that happened. He was going to find out about the dog.

He went inside. Foster was waiting for him at the door. “Jack! Jack! are you here!”

Jack came out of the kitchen. “Isn’t horrible what happened next door. Something must have set off that fire. Maybe some Christmas lights. Things like that happen all the time.”

“Jack, tell me you didn’t start that fire.”

“How could I dad?”

“You were over there, weren’t you?”

“I walked Foster. Down the street.”

“You didn’t start the fire somehow?”

Jack looked away and shook his head.

“You are lying. I can tell.”

“You don’t know me.”

“I know you are lying, so fess up.”

“Something in the garage must’ve sparked.”

Roger called Tom and told him the awful news. Tom received the call as he was sitting at Donna’s bedside.

Hearing that his garage workshop and half the house was burning down, Tom tried to gather his thoughts for a response. But they raced everywhere. After a minute of looking out the window, he said that he would fly back home. He didn’t know when he would be there. He then asked about Foster. Roger assured Tom that Foster was with them and OK.

When the call ended Tom looked over at Donna and wished for her numb state of mind. He clutched her hand, squeezed it, kissed her forehead, and then got up and began pacing the hospice hallway. He called his wife and told her the bad news. She was crushed.

They talked about what to do next. Tom said that he would fly home to assess the damage and speak to the fire marshal and the insurance adjuster. He would pick up Foster. The family would stay at Donna’s house for now. The kids were home schooled so they didn’t need to register at a new school. But all their school materials were likely lost in the fire. Tom would talk to his boss and tell him what had happened.

The next morning Tom flew home and drove to Rosy Hill Street. He parked in front of his house and gasped when he saw the charred remains. Roger saw him and came out. Jack came out behind him with Foster.

Roger didn’t know what to do and he knew what he had to do. But before he said anything, he waited for Tom to say something.

When Tom got out of the car, Foster ran up to him wagging his tail wildly. Tom bent down, picked up Foster and gave him some loving. Tom’s expression of joy changed to one of reluctant acceptance. He took in a long deep breath and sighed “Apparently, these things happen. . .” Jack began nodding “Yes.”

Tom looked over at Jack. “These things happen. . . somehow.” Jack bit his lip and turned to look down the block as if the cause of the fire was somewhere out there.

“Let me know, Tom,” Roger looked over at Jack, “what the fire inspector and the insurance adjuster say. We need to know for certain what caused the fire . . . especially with all the old Victorian houses on this street.”

The fire marshal pulled up in front of the Healy house. As Tom walked over to meet him, he whispered to Foster “One thing is certain, Foster. It’s not easy being steadfast in the curious story we’ve been cast into.”

~~

©J.A. Johnson, Kingdom Venturers, 2025, All Rights Reserved

~~~

“The Steadfast Tin Soldier” by Hans Christian Andersen was published in 1838 and is in the public domain, meaning it is no longer under copyright protection.

https://andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/TheSteadfastTinSoldier_e.html